*

Saint Bernard (1090–1153) was born at Fontaines near Dijon, France, and died in Clairvaux, France, at the age of 63. He was of a noble family and received a careful education in his youth. With his father, brother and thirty noblemen he entered the Benedictine monastery of Citeaux in 1112. Two years later he led a group of monks to establish a house at Clairvaux, and became its abbot. The monastic rule which he perfected at Clairvaux became the model for 163 monasteries of the Cistercian reform. He was a theologian, poet, orator, and writer. He is sometimes considered as a Father of the Church.

*

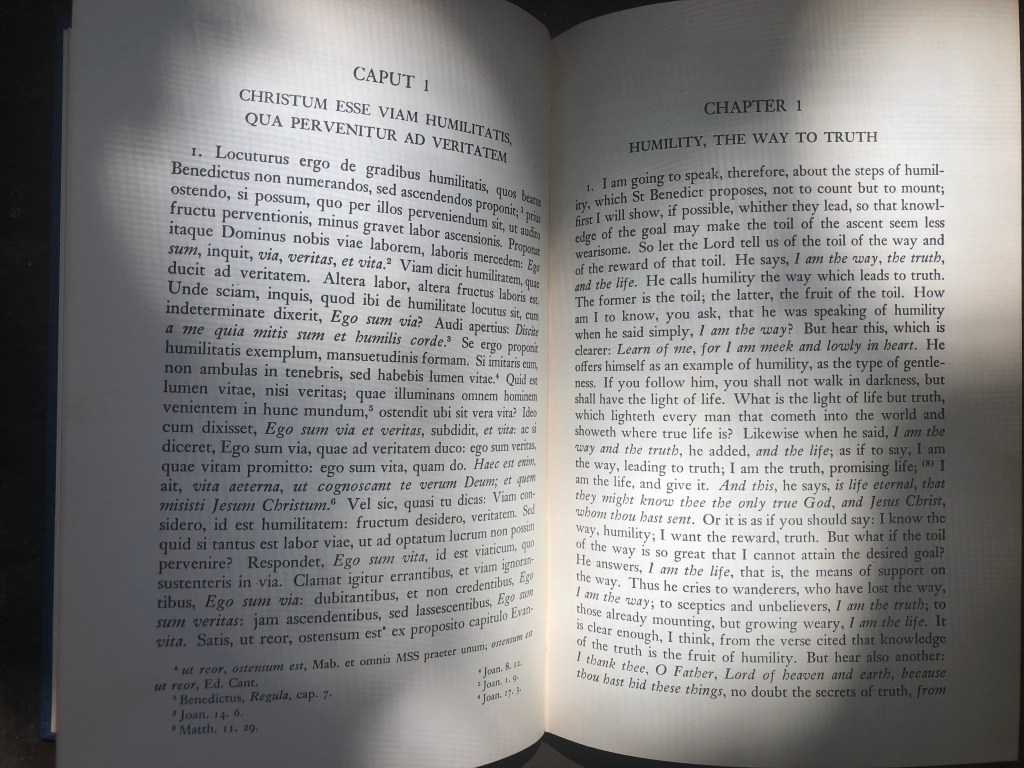

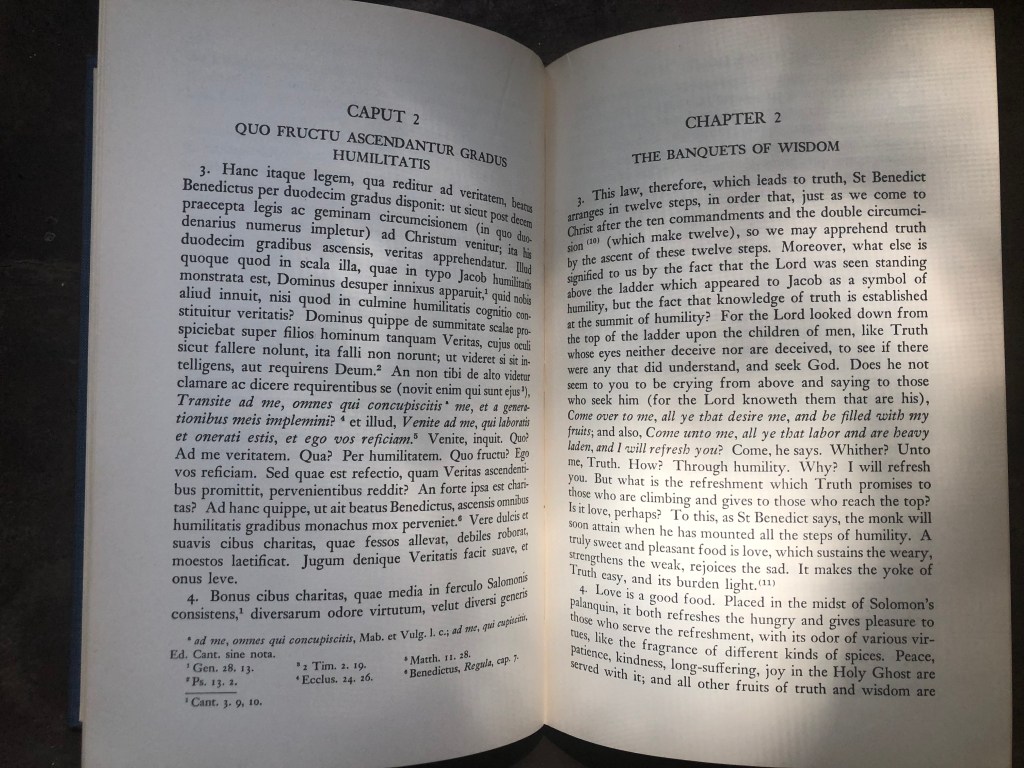

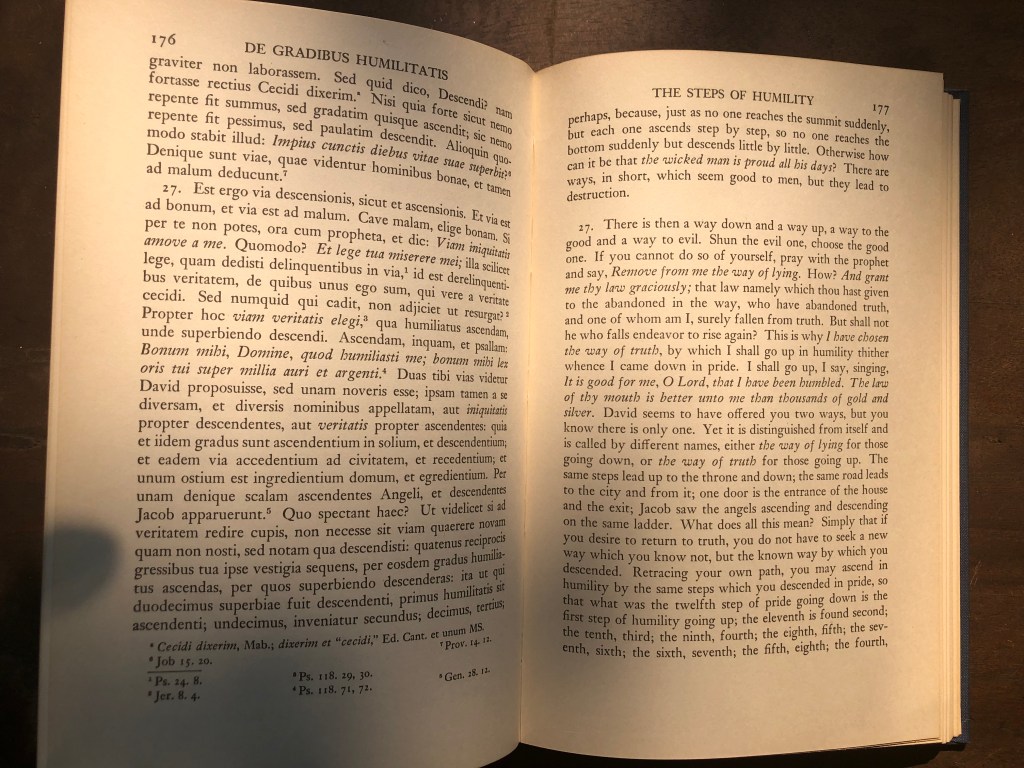

In this post we are going to give our attention to The Steps of Humility, written by Bernard of Clairvaux in 1127. At the time it was written Bernard had composed only 4 works. This work was written for one community of monks, who had asked Bernard for commentary on the 12 Steps of Humility written by Saint Benedict. Bernard instead composes this work, which ends in an articulation of the 12 descending steps of Pride. In fact there is only one set of steps, as Bernard explains, similar to Jacob’s ladder in which there are angels ascending and descending. To be ascending the steps is to be practicing Humility, while to be descending the steps is to be practicing Pride.

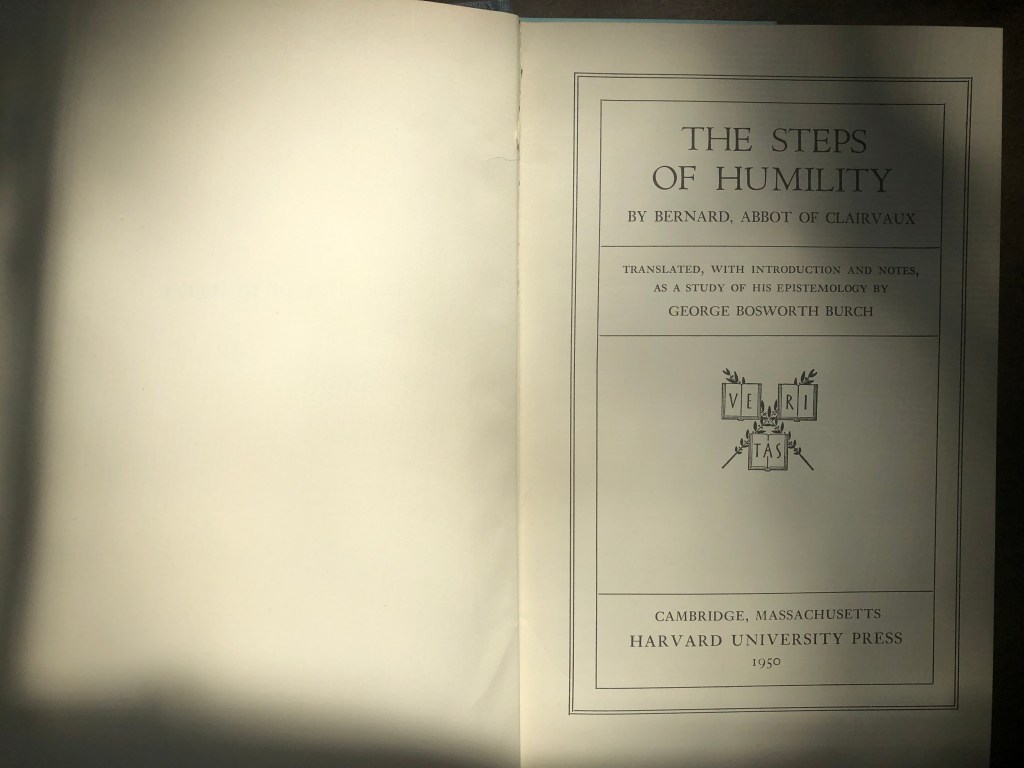

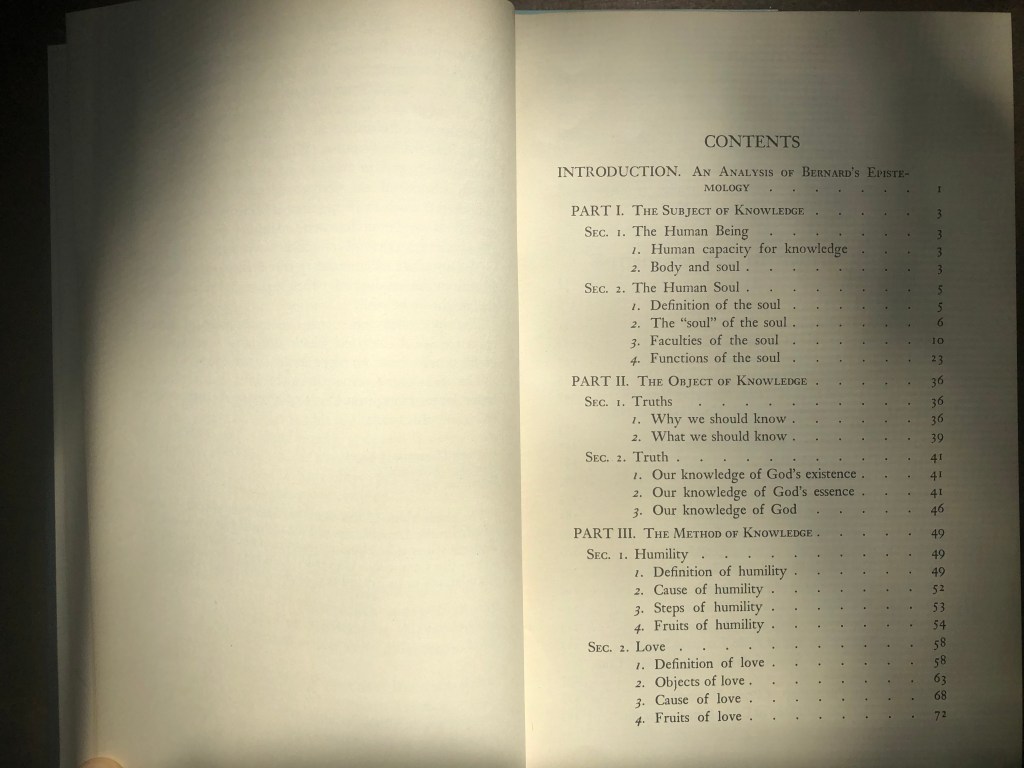

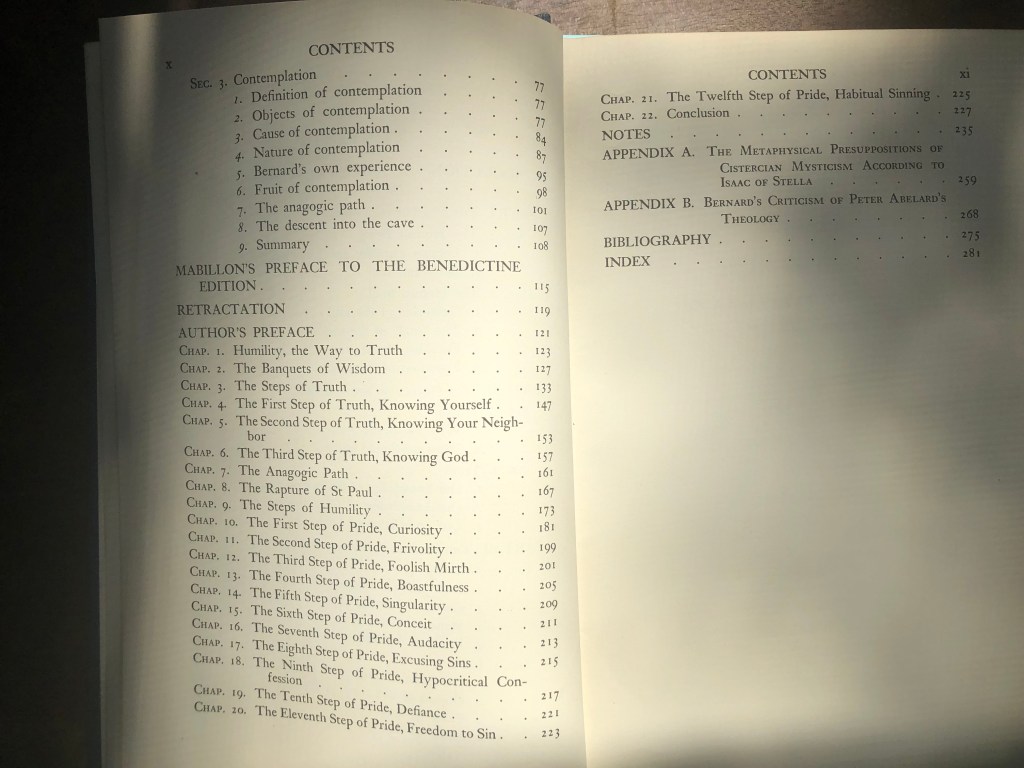

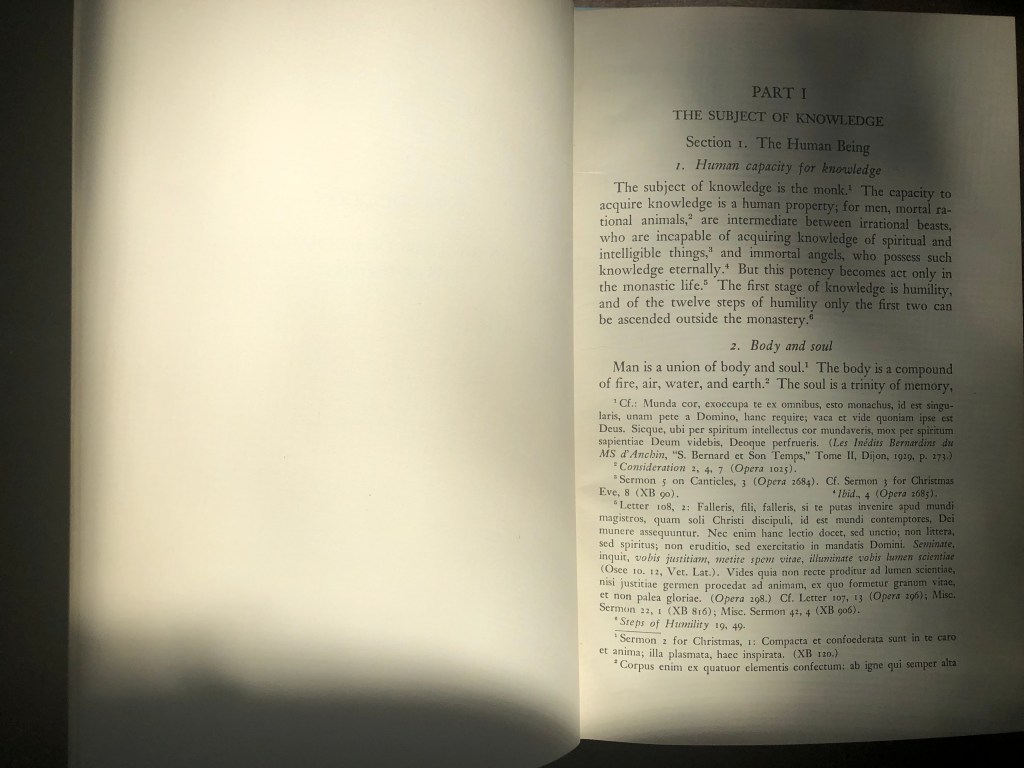

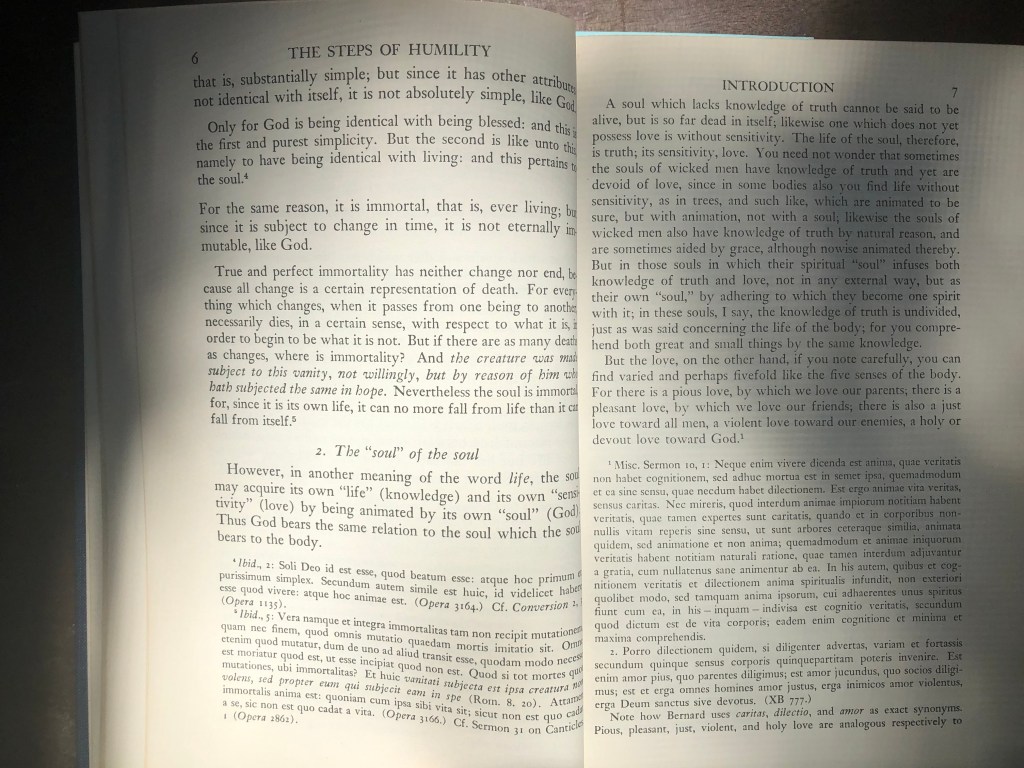

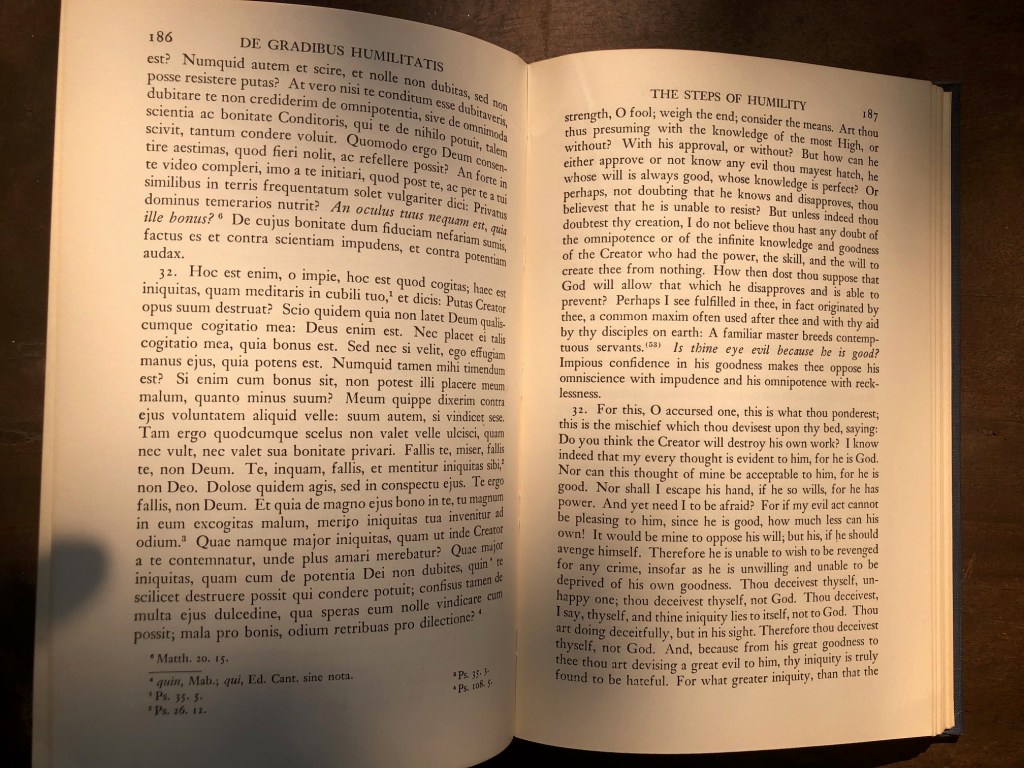

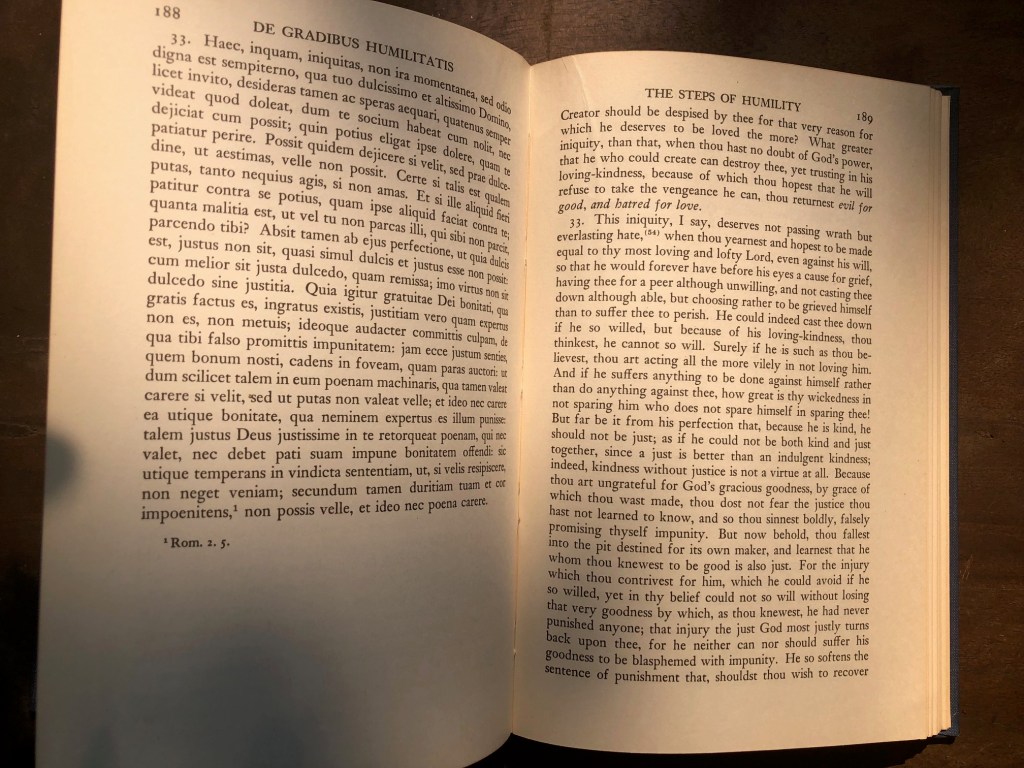

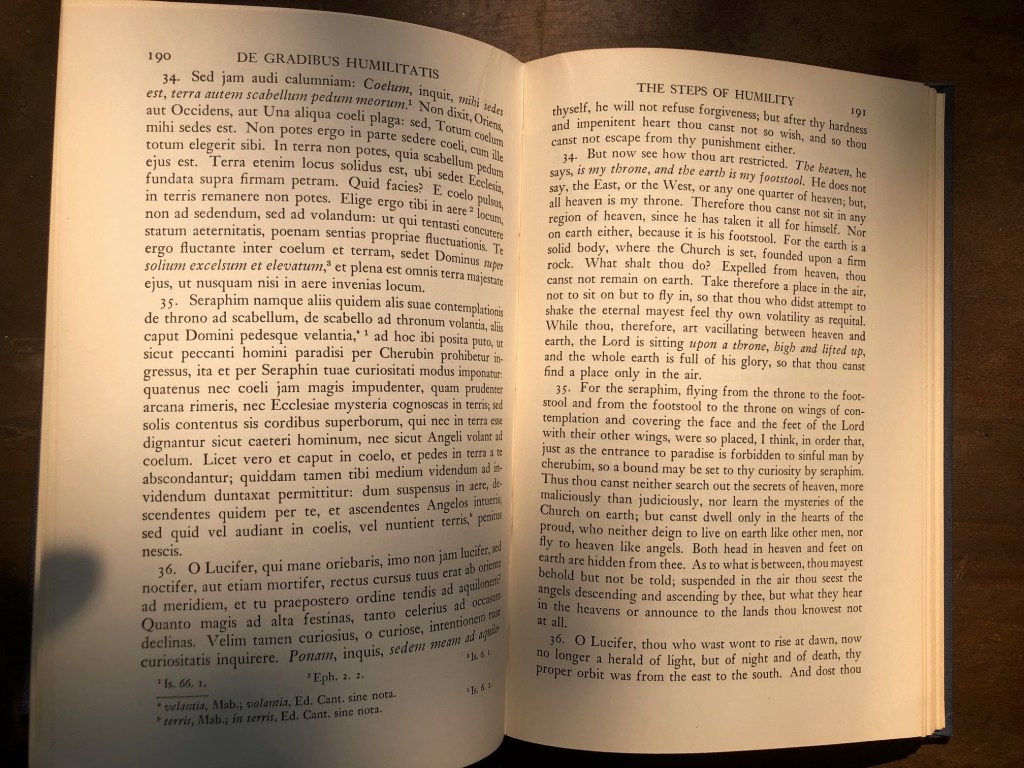

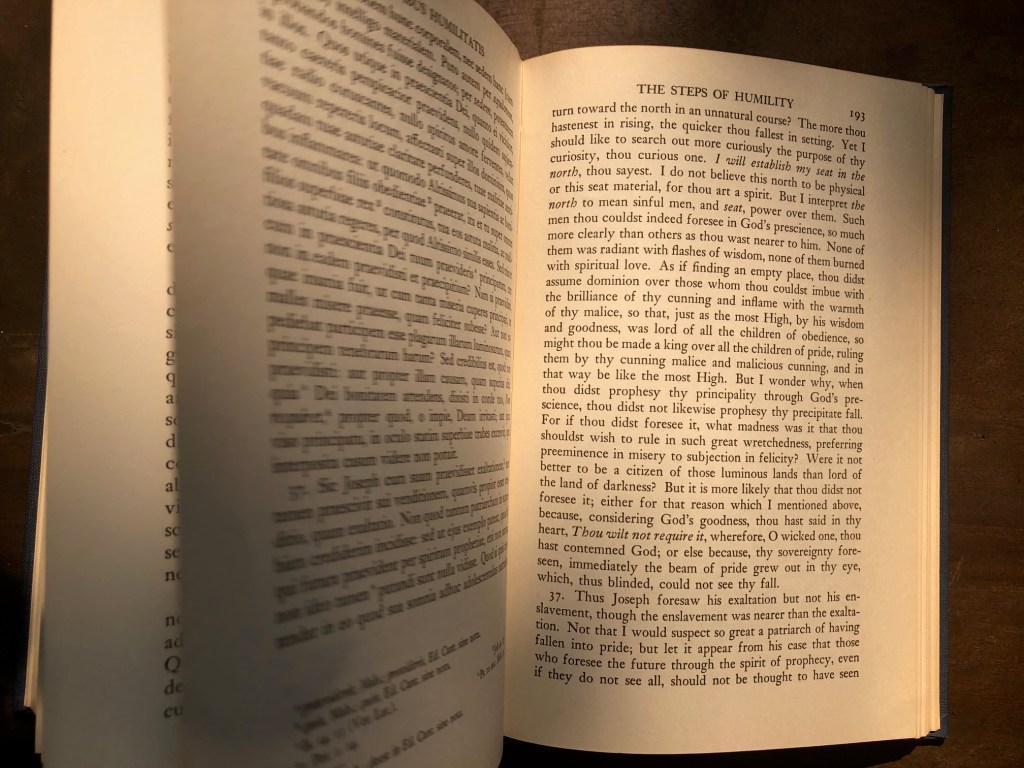

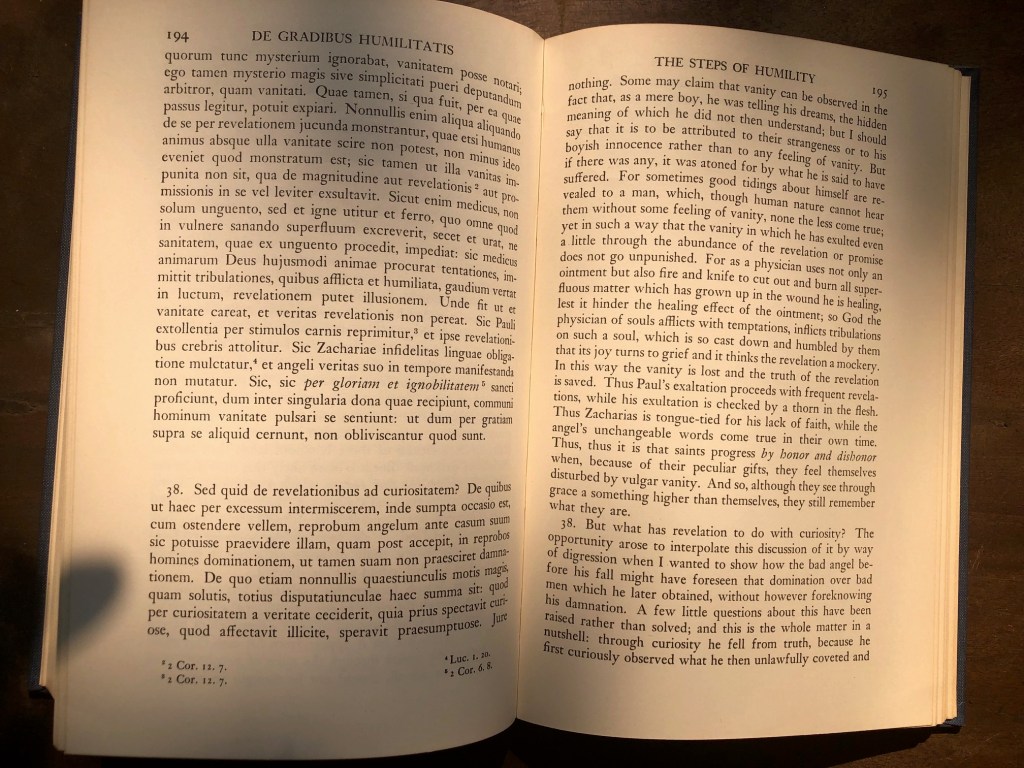

The book we will be referencing and reading from is published by Harvard University Press, 1950. Translated with Introduction and Notes, as a study of his Epistemology by George Bosworth Burch. Burch’s introduction is 112 pages long, and a very beautiful work unto itself. Perhaps there will be a separate post made on Bernard’s Epistemology as told by Burch. But for now we will focus solely on Bernard’s text, as translated by Burch. This work has appeared with slightly different titles, Degrees of Humility, The Steps of Humility & Pride. As far as I can tell these are all the same work, in different translations of the original Latin.

*

One further note before we begin.

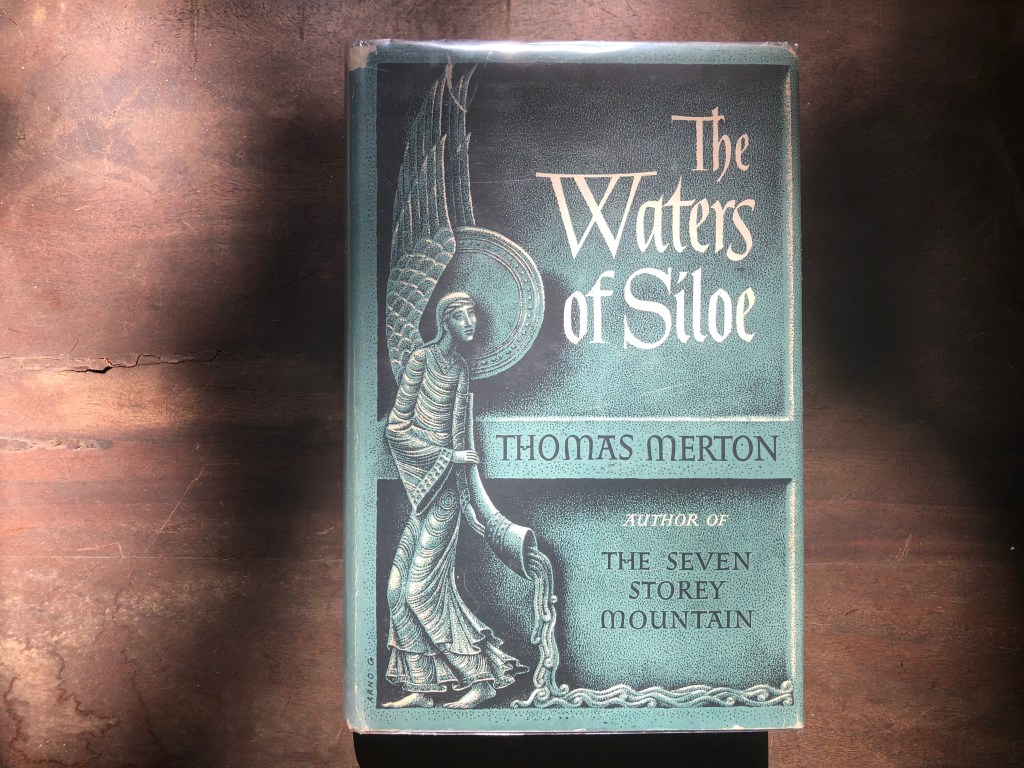

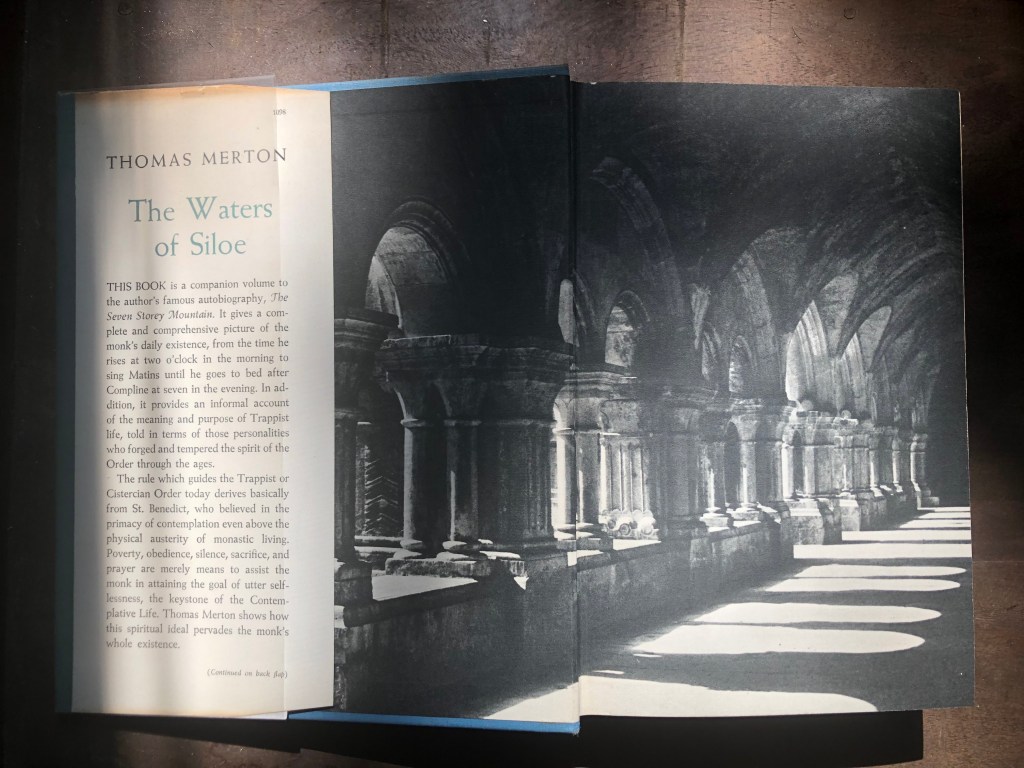

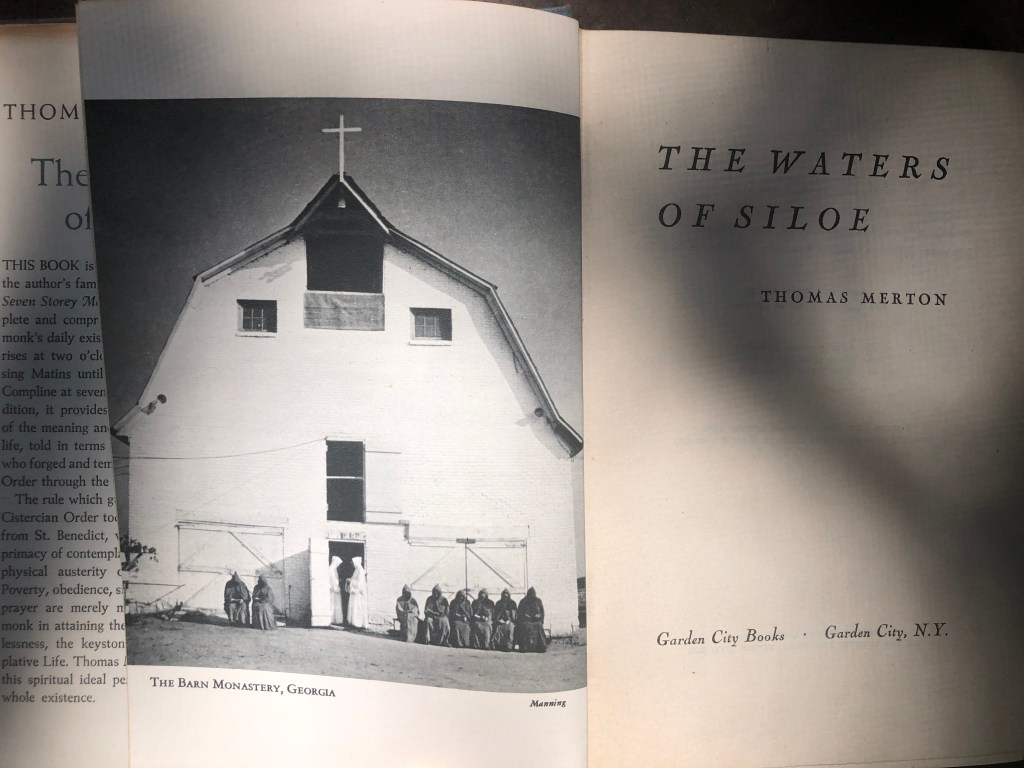

I was introduced to this text while reading Thomas Merton’s book on the history of Cistercian monasticism, The Waters of Siloe. Merton is one of my favorite writers to return to, and I would like to offer as an introduction to Bernard’s work a lengthy quotation from Merton. This is the passage that brought me to Bernard, and so perhaps it is most appropriate for this post, as an overview before we begin a close reading of Bernard’s text. Here is Merton:

“One of the early works of St. Bernard, Degrees of Humility, lays down the foundations upon which Cistercian spirituality was to be built up into a powerful but very simple edifice. The abbot of Clairvaux, fond of divisions and degrees, like most of his contemporaries, shows his monks their way to God in “three degrees of truth.” Under the guidance of divine grace, in the school of charity, in the silence of the cloister, we are to be gradually initiated into a deep experimental knowledge of the truth – first, as it is found in ourselves, then as it is found in other men and, finally, as it is in itself.

The beginning of the ascent is self-knowledge. This is more than an academic acquaintance with the names of things we have done or might be capable of doing. St. Bernard’s humility, like that of St. Benedict, is a deep and searching and, on the whole, a very vital and healthy thing, because it enters into the very recesses of the spirit. It is an experimental knowledge, a deep-seated sense not of mere shame, not of mere confusion, but also, curiously enough, of love and peace at the recognition of the human weakness and insufficiency that are in us all. It is not only intellectual, this self-knowledge, it is also affective. It is something accepted by the will. What it means, in practice, is a profound quietude and self-effacement, the disposition of a man who has gone far beyond mere callow disgust with his own failures and has begun at last to pass out of himself and attach no more importance to himself. He has become without value in his own eyes, ipse sibi vilescit. And when you recognize that something has no value, you cease to bother about it.

It is in this atmosphere of humility that the way to contemplation begins. It is only through this deep and pacifying sense of his own unimportance that the monk can be set free for the blissfully happy occupation of attending to God, Who alone is all reality and in Whom all values are sublimated, transcending every concept to which the mind has access.

The atmosphere of genuine humility is termed by St. Bernard the spiritus lenitatis (“spirit of kindness, gentleness”). Perhaps no one who has not lived in a monastery can quite savor the rich implications in those two words. No one who has not tried to follow St. Bernard and St. Benedict and enter into their peace can quite grasp the spiritual beauty and moral harmony that are contained in that idea. Yet visitors to Trappist monasteries who have been struck by the sight of some old, hard-handed, white-bearded lay brother absorbed in his job, completely unconscious of himself and radiating the innocence and prayerful gentleness of a good child, because he is obviously in communion with God even while he works, will recognize something of what St. Bernard is talking about. The spiritus lenitatis is a tenderness born of the experience of suffering, and it expands and reaches out to embrace all other men, filling our hearts with a delicate and Christian considerateness for their sufferings. When you have a broken leg, you are careful of your movements; if you have any natural sympathy, you will be just as careful of other people when you see them in the same kind of trouble. In the same way, Cistercian humility makes you very circumspect in your actions when you know your will to be weak and wounded and your intellect to be often blinded by selfishness and passion. Once you have experienced the pain of your own infirmity (and to feel the pain is the first step on the way to a cure), you soon learn compassion and a corresponding tenderness toward other people.

Now, in the common life, all the men God has brought to the monastery to be sanctified by His Spirit are thrown together with their various spiritual infirmities, their impatience, their inconsiderateness, their petty vanity, their bad tempers perhaps, and their pride and all the failings of which they are so largely unconscious. St. Bernard sees in all this a tremendous occasion for spiritual growth.

The abbot of Clairvaux seized upon this most characteristic Cistercian doctrine and gave it a crucial position in his mystical theology. The problem of mysticism is to endow the mind and will of man with a supernatural experience of God as He is in Himself and, ultimately, to transform a human soul into God by a union of love. This is something that no human agency can perform or merit or even conceive by itself. This work can be done only by the direct intervention of God. Nevertheless, we can dispose ourselves for mystical union, with the help of ordinary grace and the practice of the virtues. We have just seen that, for St. Bernard, the two principal steps in this active preparation were humility and charity, or meekness and compassion. They both are “experiences” of the truth: the truth about ourselves and the truth about others. But since contemplation is an “experience” of God by connaturality, by union of love, St. Bernard sees that a nonnatural appreciation of the sufferings and sentiments of other men is an excellent preparation for the mystical knowledge of God in the obscure “sympathy” of infused love. After all, contemplation is an intimate knowledge of God that flows from a loving union with His will. And God Himself has told us that the ordinary way to that union of wills with him is union of wills with other men for His sake. “Let us love one another, for charity is of God. And everyone that liveth is born of God, and knoweth God. He that loveth not, knoweth not God, for God is charity. . . . He that loveth not his brother whom he seeth, how can he love God whom he seeth not? . . . If we love one another God abideth in us, and His charity is perfected in us.”

St. Bernard gives another reason why this charitable compassion is a perfect preparation for mystical prayer.

It is, he says, because the Holy Ghost takes a more transcendent part in the act of such a soul and intervenes more directly in the work of preparation. He shoes us how, in the vicissitudes and trials of community life, the Spirit of God, the Spirit of Unity, is at work in the souls of the monks, visiting and purifying each will with fire and sweetness, to make it merciful, dignanter visitans, suaviter purgans, ardenter efficiens misericordem facit. The final result, in the soul that submits to this action of God, is that the will softens and is made smooth and pliant and tractable, like well-greased leather. It can be “stretched,” says the saint, even to the extent of loving its enemies. Then it is ready for the higher experience, the supernatural union in which it will pass our of itself antirely and be absorbed in the pure love of God.”

Pages 21-25

The Waters of Siloe

Thomas Merton

*

And now, we will begin a close reading of St. Bernard’s text….

*

CHAPTER 1

HUMILITY, THE STEPS TO TRUTH

*

“Knowledge of the truth is the fruit of humility”. Bernard’s text begins at the end, so to speak. He intends first to show where the steps of humility lead, so that “knowledge of the goal may make the toil of the ascent seem less wearisome”. The text operates the way inspiration operates. When one receives an inspiration, one understands the end, and then sets out on the journey of toiling to make the inspiration manifest in one’s life in the world. In this way the book opens with knowledge of an end already known. In some sense the text is speaking from the dual perspective of present & eternal future, using as demonstration the Lord who has already toiled through the Steps of Humility and received the fruit of Truth. If one chooses to follow the demonstration of the Lord, he too will receive the reward of that toil, that is, one shall have the light of life.

“I am the life, that is, the means of support on the way. Thus he cries to wanderers, who have lost their way, I am the way; to skeptics and unbelievers, I am the truth; to those already mounting, but growing weary, I am the life.”

“Humility is that thorough self-examination which makes a man contemptible in his own sight.”

This idea of Humility as self-examination is perhaps the core of Bernard’s teaching, and will be elaborated on in future chapters. From the bread of sorrow to the steps of Pride. The text begins to facilitate this self-examination; each step of Pride is later articulated as a tool to be applied during self-reflection, to assist one in recognizing the faults and self-deceptions that would lead to the descent of Pride.

The chapter ends by naming the Lord as the lawgiver who commands those that have lost their way to follow the way of humility that leads to Truth. “For they are surely abandoned who have abandoned Truth”. This double abandonment is interesting. One who abandons Truth becomes abandoned. The title of lawgiver for the Lord is significant. The double abandonment and title of lawgiver raises the notion that while one is within the law of the temporal world or of the State one is abandoning Truth and is therefore abandoned by the higher law of the Lord. There are concentric rings of law and authority. The human, worldly, temporal law exists within the higher law and transcendent authority of the Lord. One would have to abandon the temporal law of the world and follow the eternal law of the Lord in order to recover salvation. Abandon the Truth and be abandoned, abandon the world to be saved by Truth.

It’s worth noting here that Bernard is writing for contemplative monks. It is in the purity of heart of contemplation that we learn to abandon the world.

*

CHAPTER 2

THE BANQUETS OF WISDOM

*

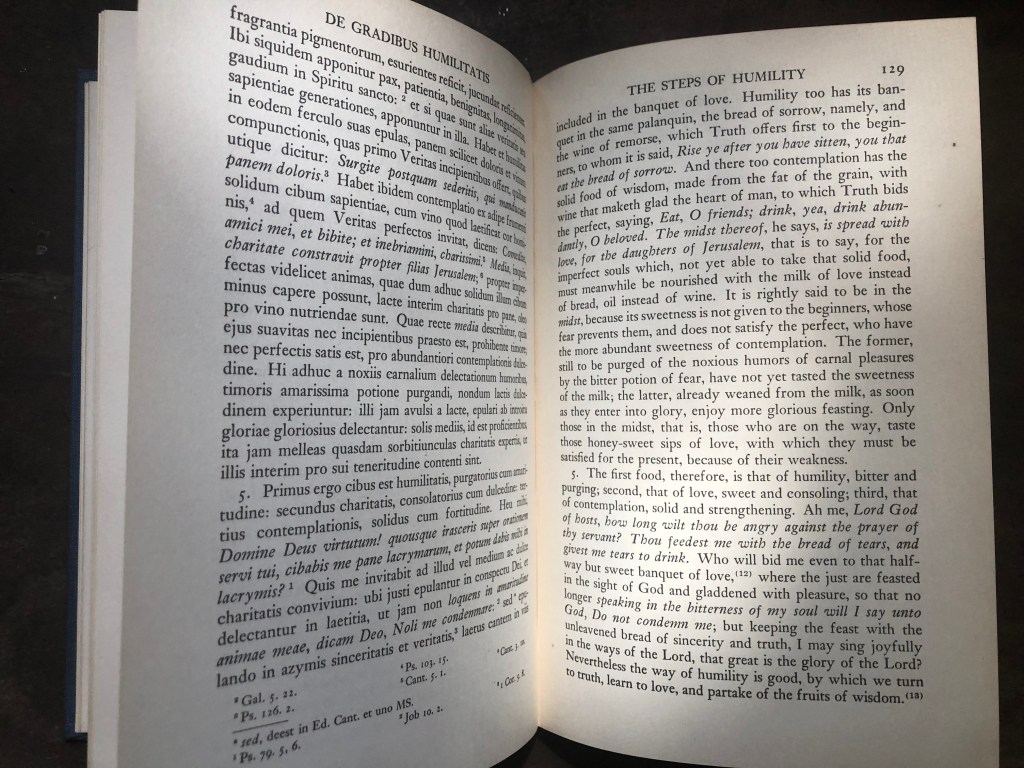

We begin chapter two reiterating that we are attempting to meditate on the law that leads to Truth, and this law is the steps of Humility. There is the beautiful image of the eyes of the Lord looking down from the top of the ladder, “whose eyes nether deceive nor are deceived, to see if there were any that did understand, and seek God”. The way up is through humility, and through humility we understand Truth and learn to receive love, and we are refreshed by this love. This love we learn to receive through humility is like a food, teaches Bernard, “Peace, patience, kindness, long-suffering, joy in the Holy Ghost are served with it”.

But Humility has its own banquet. “The bread of sorrow, and the wine of remorse”. This concept of the bread of sorrow is essential to understand. For on the spiritual path, we can not even begin our ascent until we consent to eating the bread of sorrow. Which is to say, we must look within and recognize the ways in which we are fallen, flawed, sinful and complicit in the evil ways of the world. We must take an honest moral inventory of ourselves, we must eat this bread of sorrow, and drink the wine of remorse to understand how we have separated ourself from God. Humility is the love of truth, and humility begins with contempt for the self in order to discover the love of God, to discover a love beyond ourselves, this love of God leads us to contemplation. Until we consent to eating the bread of sorrow we remain blind to our separation from God, lost in a world of imperfect relativity, self-deception and intellectual rationalization of our condition. God is Absolute Truth and perfection. Consenting to eat the bread of sorrow is recognition that have committed acts that have separated us from God, but is also the beginning of our way back to union in Love . Before we can enjoy the sweetness of Love, we must first pass through the purging bitterness of sorrow and comprehend our own affliction. Once we are purged by recognition of our separation and we begin the toil of the ascent through humility, we become capable of receiving the sweet and consoling Love, which prepares us for the next step of contemplation. And contemplation is “solid and strengthening”. We end the chapter once more by remembering that “knowledge of truth is the perfection of humility”, revealed to the humble. We ascend by steps.

*

CHAPTER 3

THE STEPS OF TRUTH

*

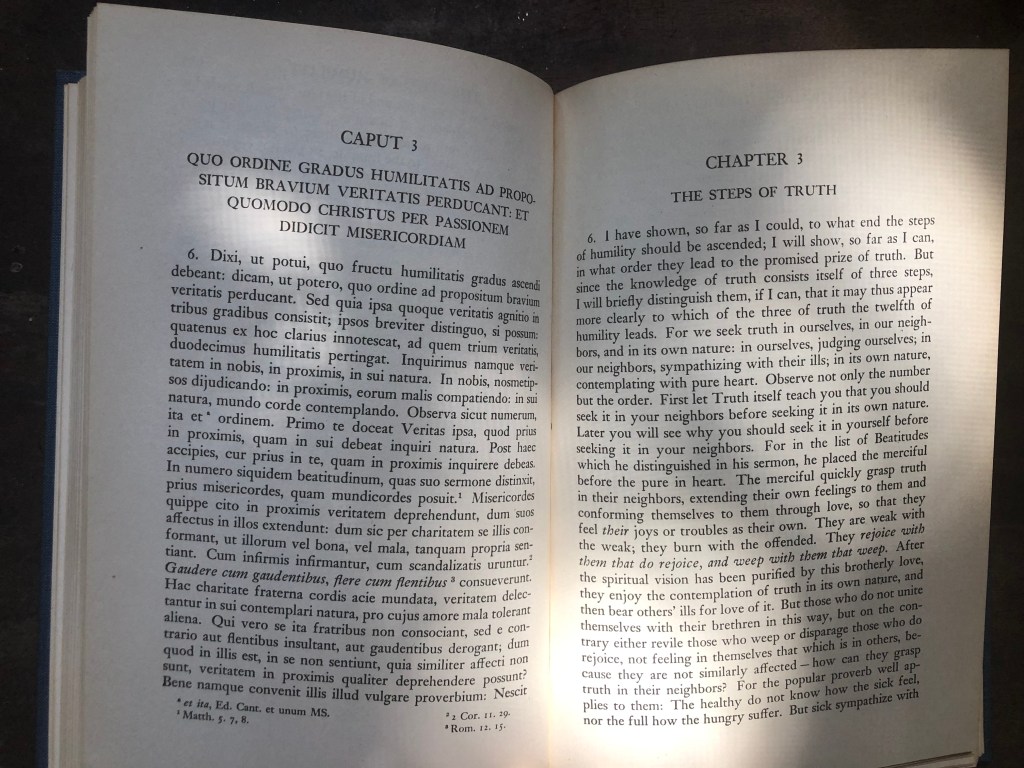

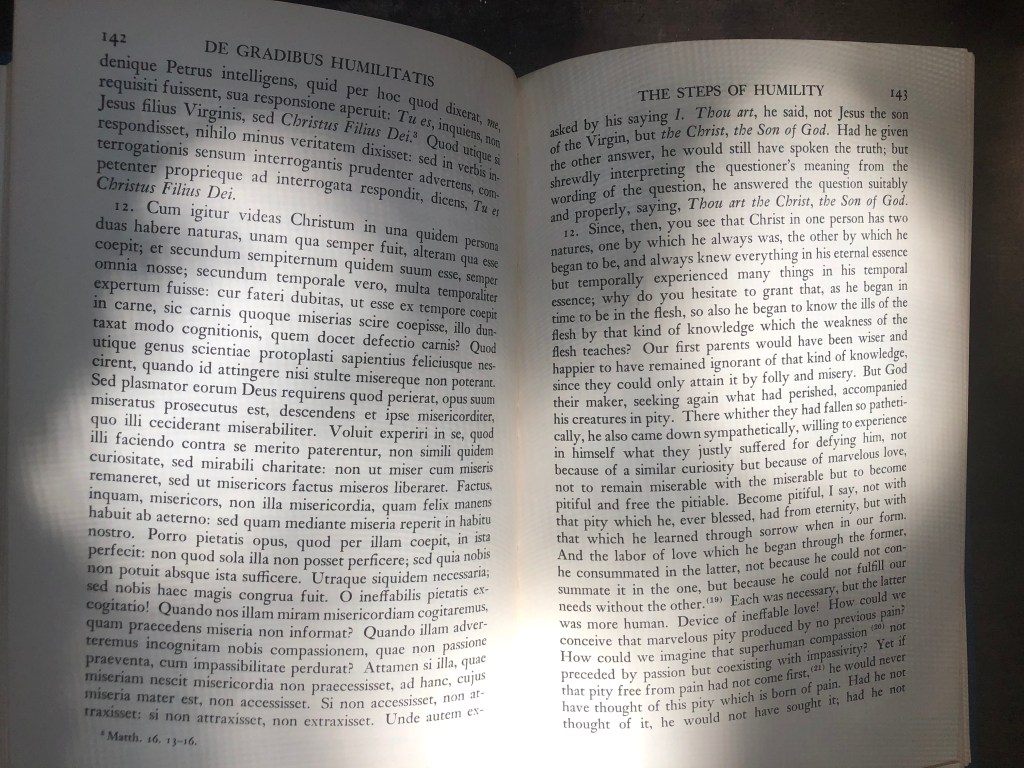

The Knowledge of Truth is distinguished into three steps: ourselves, our neighbor, and its own nature. The order of the steps changes as one advances on the journey to Truth. First we should seek truth in our neighbors, later we first seek it in ourselves. Bernard describes the empathy we might have for our neighbors, “extending our feelings to them”, feeling their joys or troubles as our own. This process of going beyond one’s self to extend our feelings in mercy for our neighbors is a way to purify the spiritual vision that will be later used during contemplation. Feeling the misery of the other will allow us to recognize our own misery, we begin to recognize other minds in our own, which prepares us for compassion and the ability to help the other due to the nature of shared experience and shared mind. This is the path of the empathetic healer, who is able to feel another’s pain and heal it from within, the greatest example of this being our Savior, who took on the suffering of the world and thereby learned mercy.

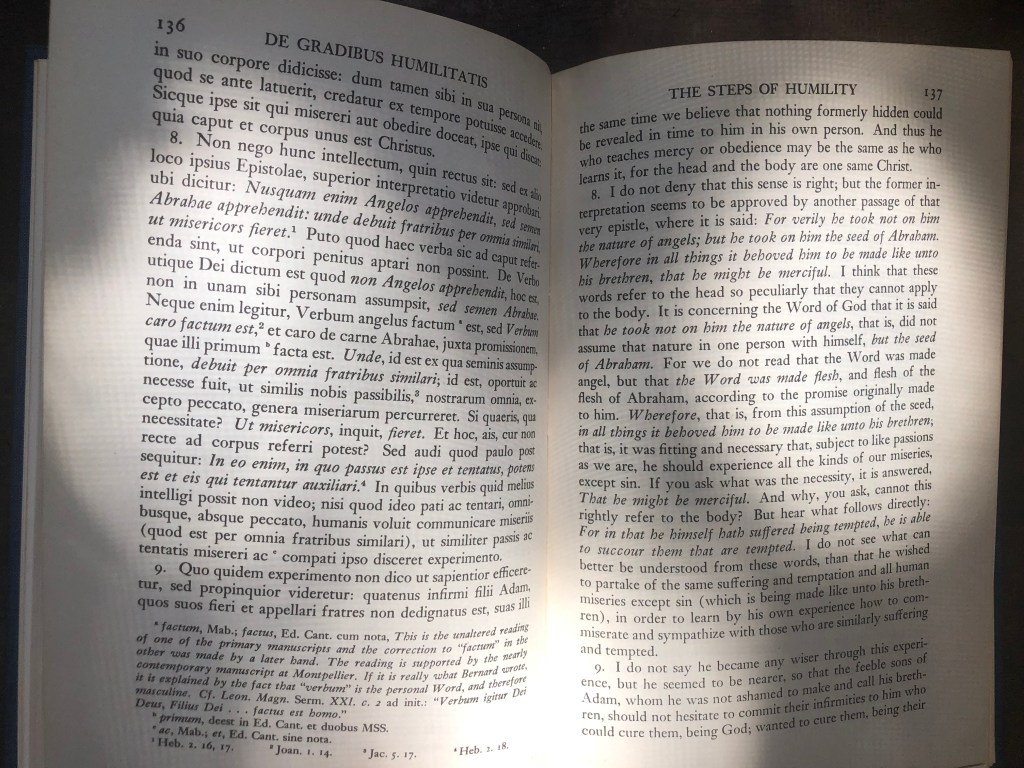

There is an important distinction drawn between the body of Christ and the divine mind of Christ. It is the body that learns obedience through suffering. Christ through obedience of mind to God first empathetically processes the suffering of man in his body and secondly leaves us the example of obedience to God that we can follow and strive to imitate. From these thoughts we understand the importance of Christ being made flesh. “For in that he himself hath suffered being tempted, he is able to succor them that are tempted”. Christ was tempted, but without sin. Christ suffered in his body so that he might deliver mercy unto us. Christ “hath borne our griefs and carried our sorrows, and because of his own passion we are sure of his compassion for us. Because of the passion, Christ’s mercy becomes both temporal and eternal.

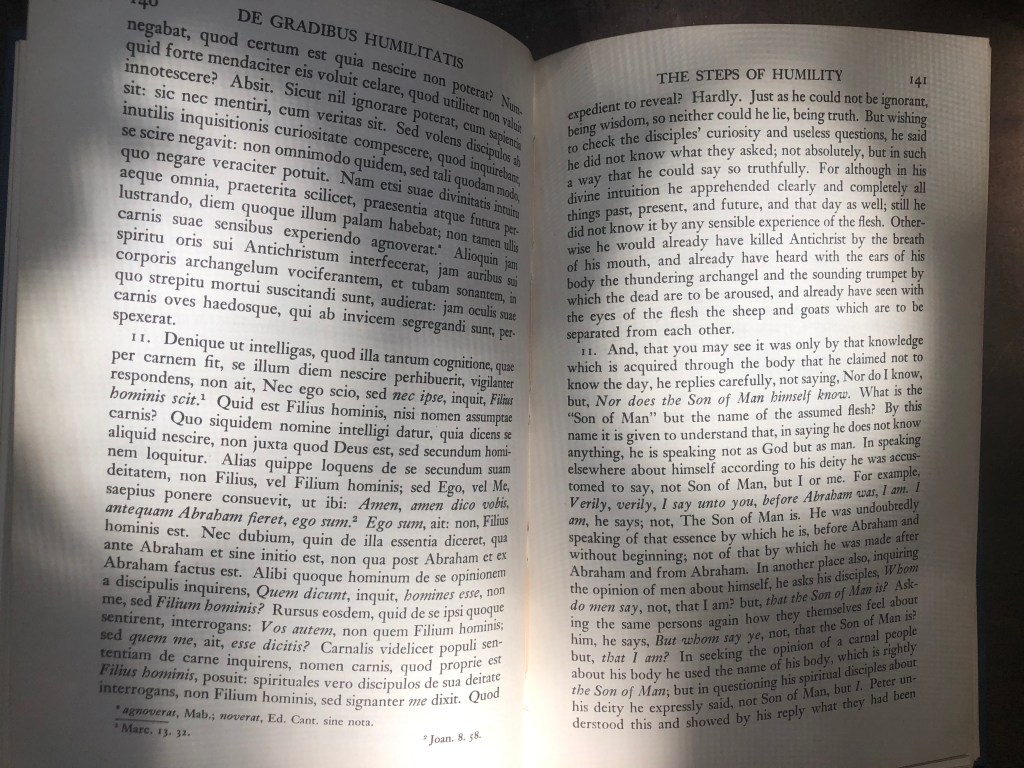

Bernard draws our attention to how Christ at times refers to himself as the “Son of Man” and other times as “I” or “me”. Bernard sees this as a distinction between the temporal body of Jesus, “Son of Man”, and eternal mind of divine Christ, “I”. When we pray, when we contemplate, it is useful to bare in mind the structure of this double truth of the joy of God & the suffering of Christ. In the relative temporal body of the Son of Man there is suffering & in the eternal divine mind of God there is joy. Both exist in simultaneity in the structure of a double truth. Another way of stating this is the double truth of the relative & absolute. Both relative truth and absolute truth exist simultaneously, overlapping in a certain sense. Every thing in the world occupies itself in relative relations and states of affairs, while the true potential of any thing in the world is known only by the absolute awareness. Our human existence is in a world of relative truth, whereas God alone knows Absolute truth. Therefore it can be said that God does not understand our suffering, rather our finite suffering is permeated by God’s infinite joy.

*

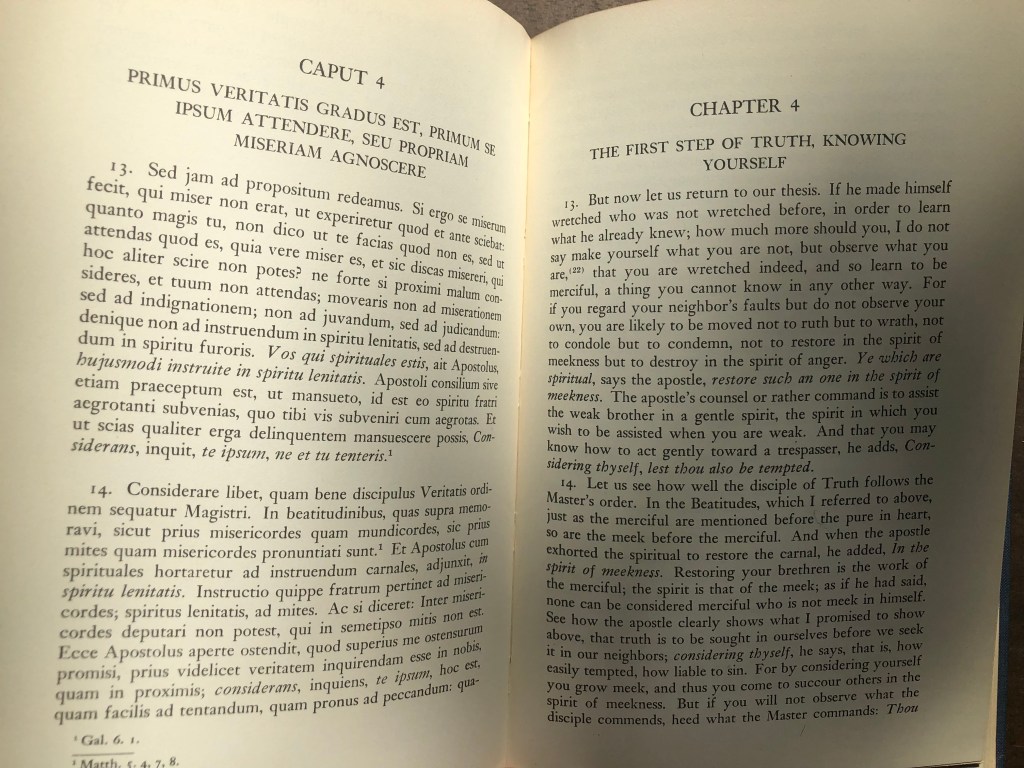

CHAPTER 4

THE FIRST STEP OF TRUTH, KNOWING YOURSELF

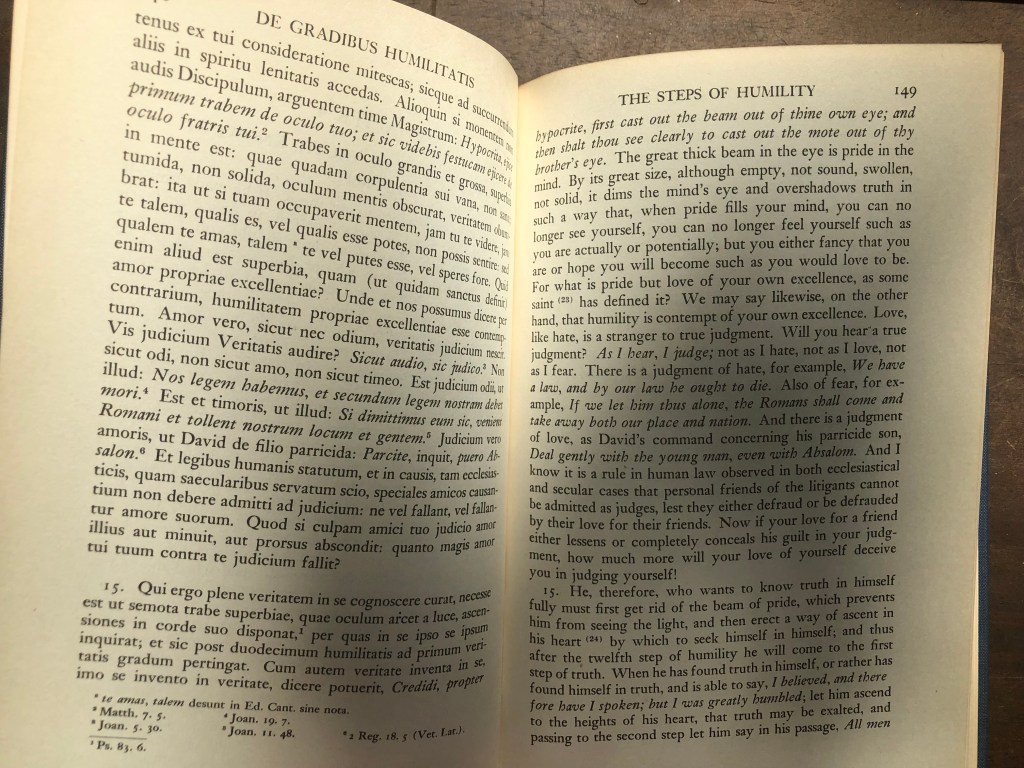

We now go deeper into the first step of Truth, to know yourself. Bernard is teaching that we must look at our own wretchedness, and observe our own faults and failings so that we may become compassionate to the faults and failings of others. Knowledge of our own sins will help us to love our neighbor. This is the cultivation of the spirit of gentleness. By experiencing the suffering of our own wretched state, we become compassionate and gentle with the suffering of our neighbors. “Restoring your brethren is the work of the merciful; the spirit is that of the meek”. When we consider ourselves deeply and honestly we see how we have been tempted and failed, how we are liable to sin – and in the depth of this recognition we rediscover compassion for the other who has failed and sinned. It is Pride that prevents us from seeing ourselves as we truly are, and therefore it is Pride that keeps us from truth and compassion. It is only after we have been humbled by recognition of our own fallen wretchedness that we become capable of both giving and receiving true love, rather than occupying the false love of one’s own excellence that is Pride.

*

CHAPTER 5

THE SECOND STEP OF TRUTH, KNOWING YOUR NEIGHBOR

It is by passing outside of ourselves and clinging to Truth that we are able to judge ourselves. “He that increaseth knowledge increaseth sorrow, so as to say, broadly but truthfully, All men are false.” The mistake that is often made is to exclude oneself from the eyes judgement that see all others, this is arrogance and pride – all have come short of the glory of God, and none are exempt from this status. “The prophet does not exclude himself from the common passion, lest he be excluded from the compassion”. To exempt oneself from guilt is to exempt oneself from mercy. The example is given of the Pharisee, “who complains of all, except himself, thinking I am not as other men are.” The Pharisee has not yet found truth, for he has not yet learned to see himself from the position of truth. Truth causes one to know, and to know means to have contempt for what one is. Once this mode of humility begins one strives for what is beyond one’s self, one recognizes that they are in need of the grace of God, that in fact they would be nothing were it not for the overflowing abundance of God’s grace and love. We learn how to be merciful by recognizing the mercy that has been bestowed upon us from the most high.

*

CHAPTER 6

THE THIRD STEP OF TRUTH, KNOWING GOD

After we have gone beyond ourselves to Truth, and know ourselves worthy of contempt, we discover compassion for our fellow man, and recognize we are in need of God’s grace and mercy. We no longer plead weakness or ignorance, we are fully aware of the ways in which we are sinful, and we pray for mercy. We may from this position find passage to contemplation. Weeping, and hungering for justice, the eye of the heart is purified.

“Blessed are the pure in heart: for they shall see God. Since there are therefore three steps or states of truth, we ascend to the first by the toil of humility, to the second by the emotion of compassion, to the third by the ecstasy of contemplation. In the first, truth is found harsh; in the second, loving; in the third, pure. Reason, by which we examine ourselves, leads us to the first; love, by which we sympathize with others, entices us to the second; purity, by which we are listen to invisible heights, snatches us up to the third.”

This structure of three steps to ascension resemble the stages of ascension in the design of Dante’s Divine Comedy. The first guide is Virgil, representing enlightened reason, then Beatrice, representing love, and then Bernard, representing purity.

*

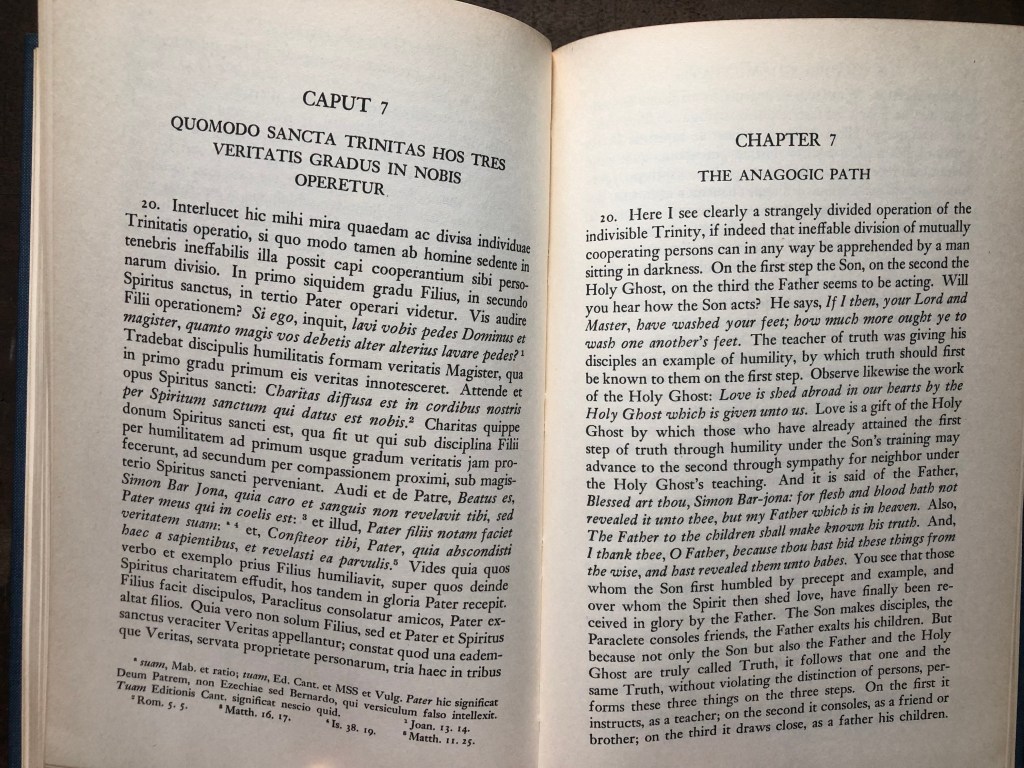

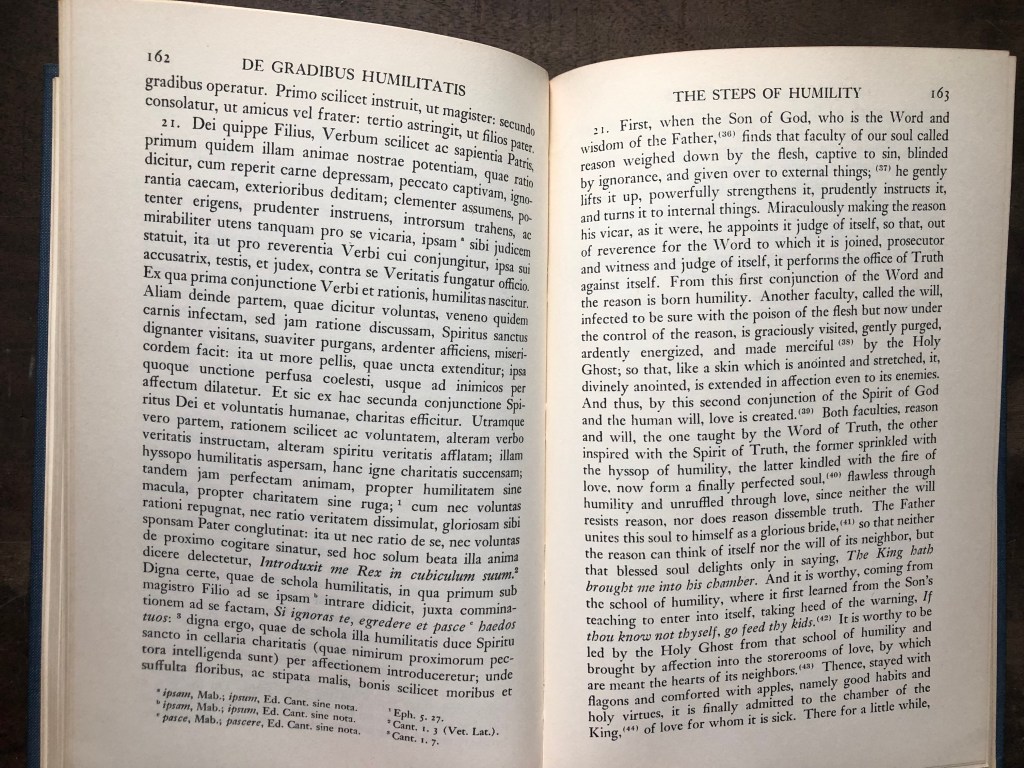

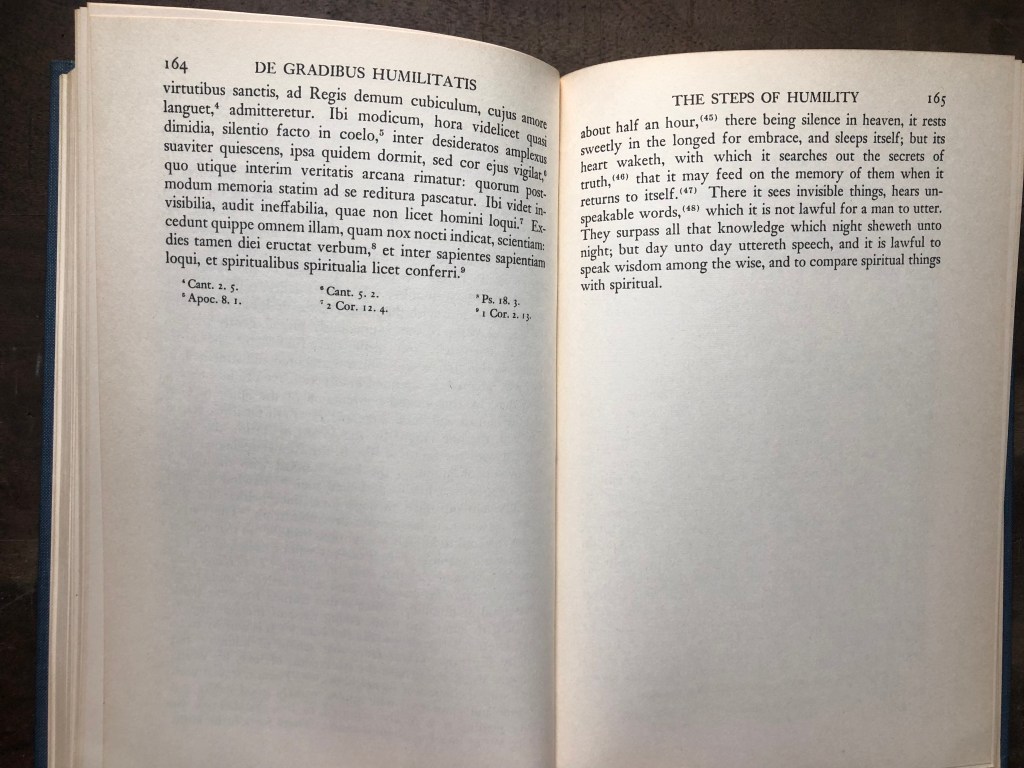

CHAPTER 7

THE ANAGOGIC PATH

Bernard draws a comparison between the three steps toward truth and the Trinity. The first step is Son, second is Holy Ghost, and third the Father. The first step is humility as demonstrated by the Lord when he washes the feet of his disciples. The second step is the love that is shed in our hearts, the gift of the Holy Ghost, this is the compassion and love that we give to our neighbors. The third is the Father, the Truth that resides in heaven from which all things true are made known.

The first step is instruction, the second consolation, the third is uniting the soul to truth.

*

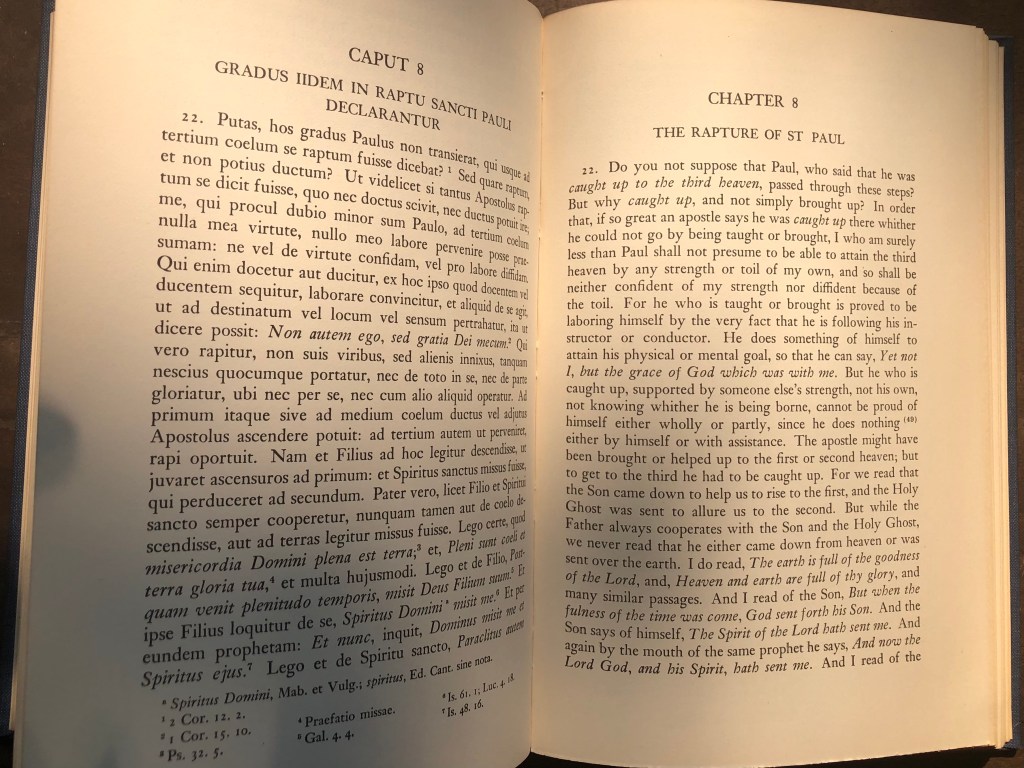

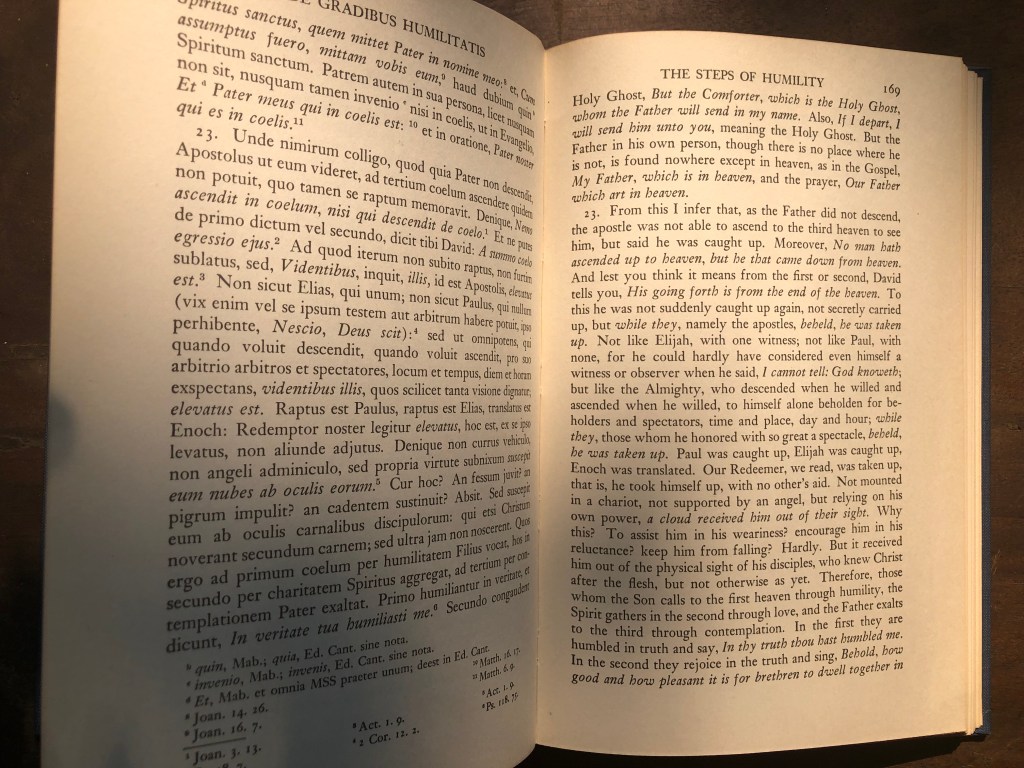

CHAPTER 8

THE RAPTURE OF St. Paul

We open this chapter in wonder at the particular notion of St. Paul being caught up to the third heaven, rather than taught how to reach it, or brought there by his own will. The important recognition is that it is not by our own strength that we ascend, but by the grace of God. Bernard elaborates the theology of the Trinity in relation to the steps. The first heaven and first step can be taught by the Son through humility, the second heaven can be reached with the spirit of the Holy Ghost that gathers with love, but the third Heaven is of the Father who has never descended and to reach the third heaven one may only be caught up by the Father while in contemplation.

- Humility

- Love

- Contemplation

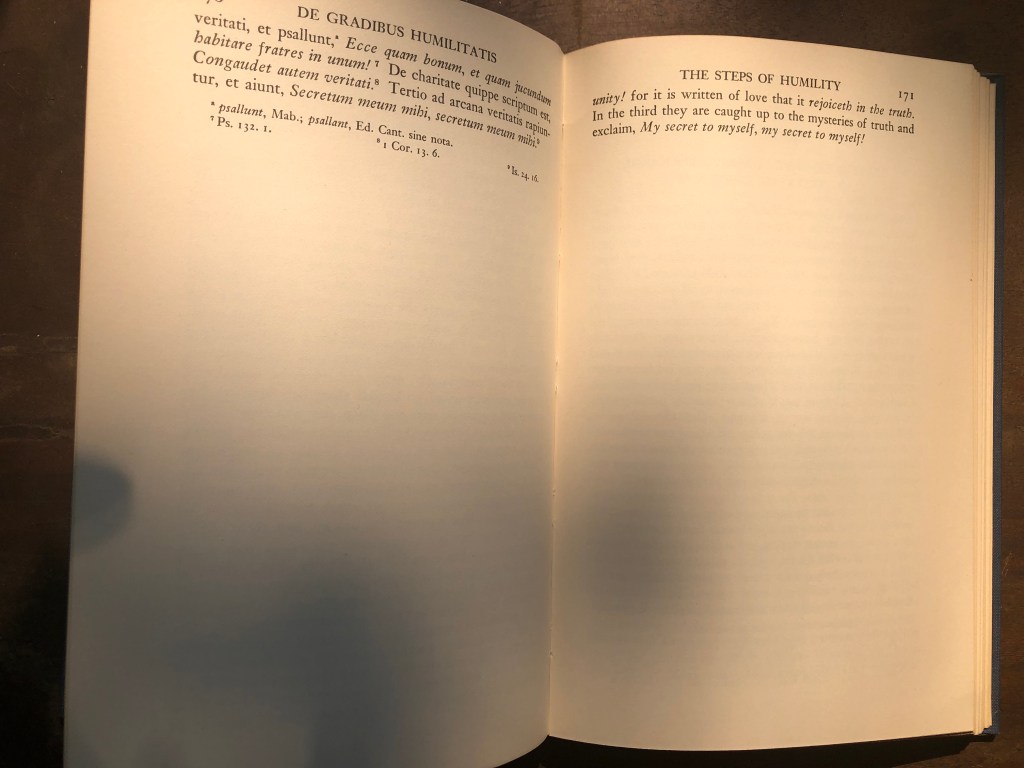

“In the third heaven they are caught up to the mysteries of truth and exclaim, My secret to myself, my secret to myself!”

*

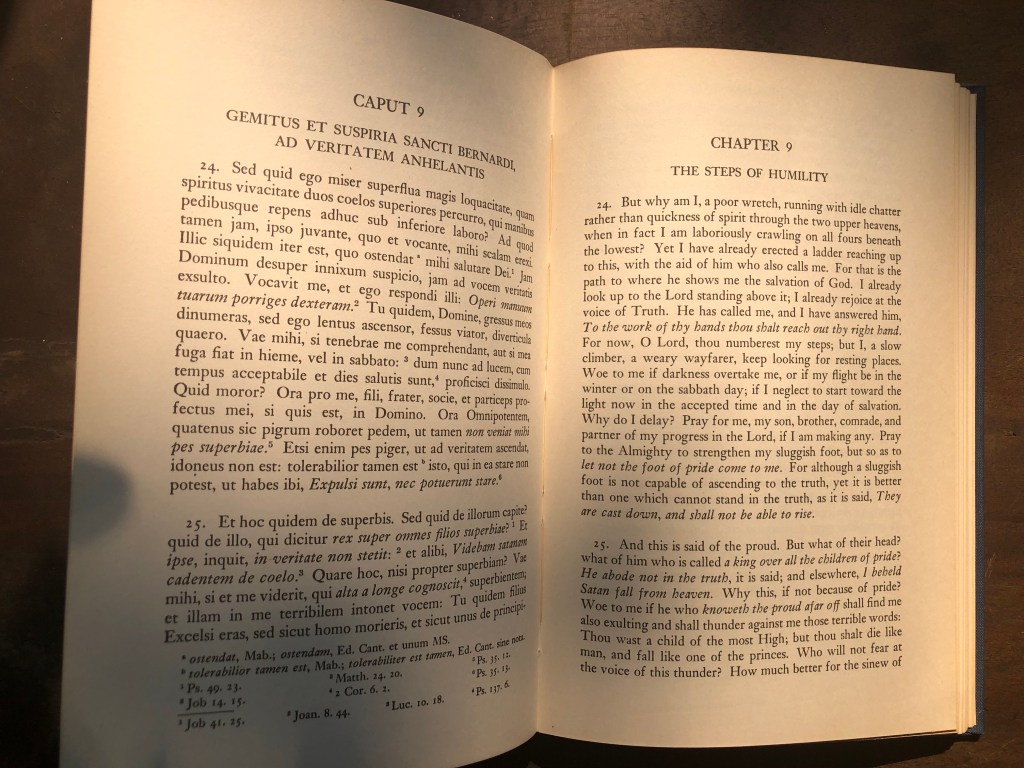

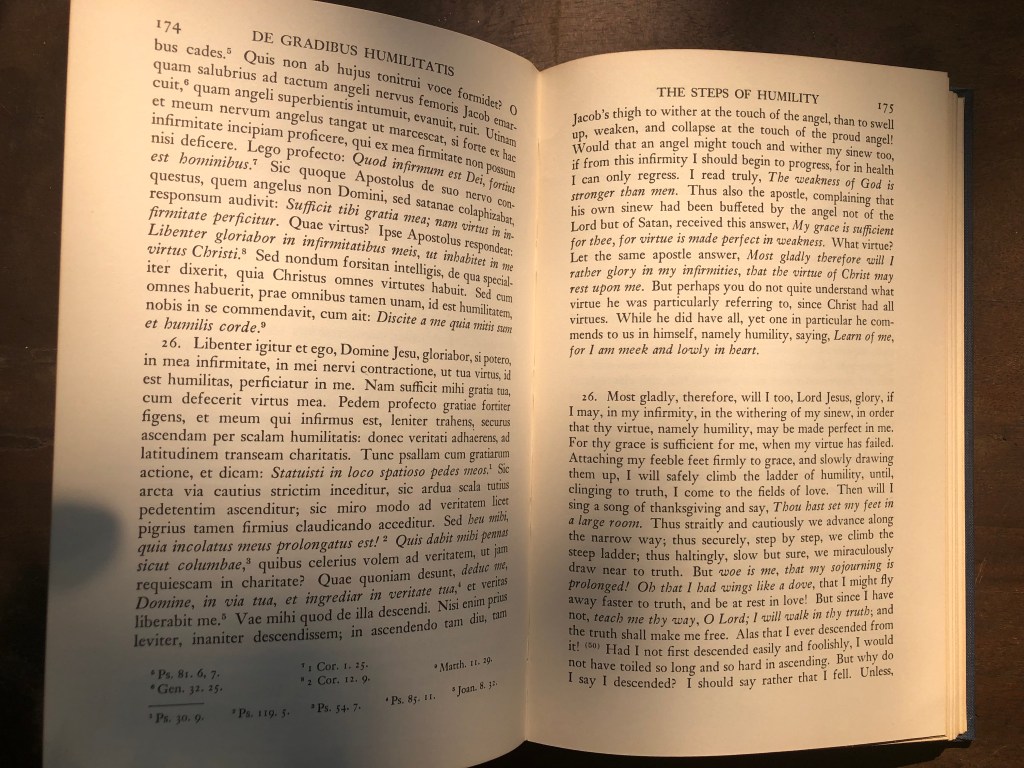

CHAPTER 9

THE STEPS OF HUMILITY

My grace is sufficient for thee, for virtue is made perfect in weakness.

This chapter is the turning point of the book. The steps of humility are seen as a ladder, the very same steps of Humility that ascend are also steps of Pride that descend. Bernard is preparing to articulate the steps of Pride.

*

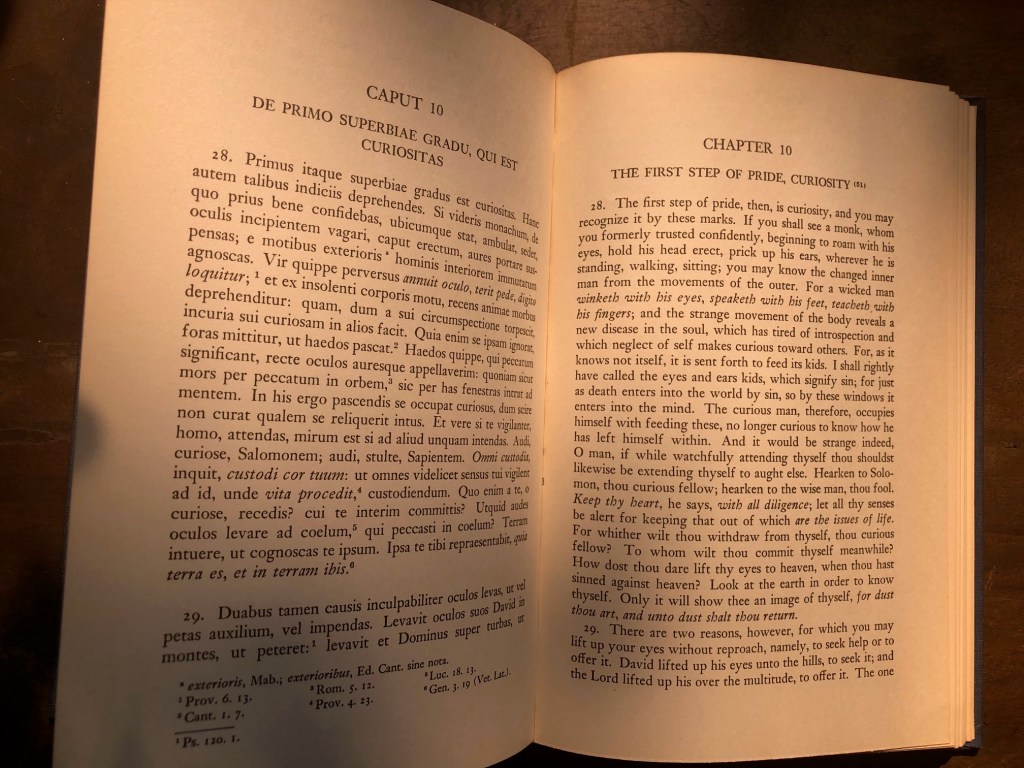

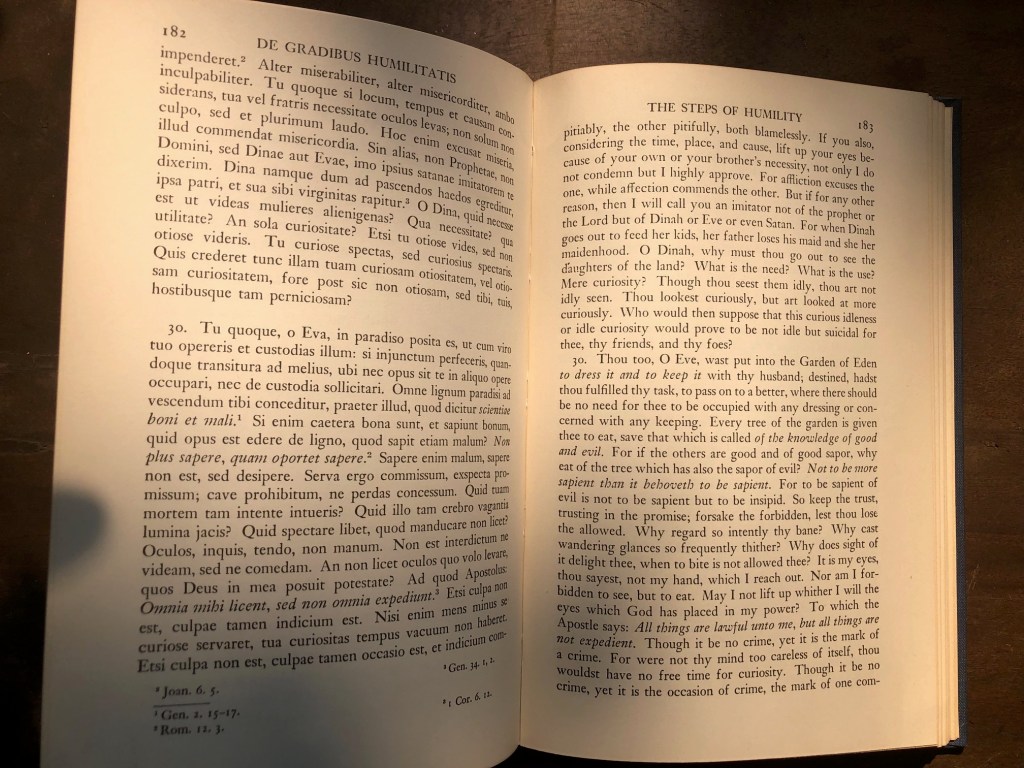

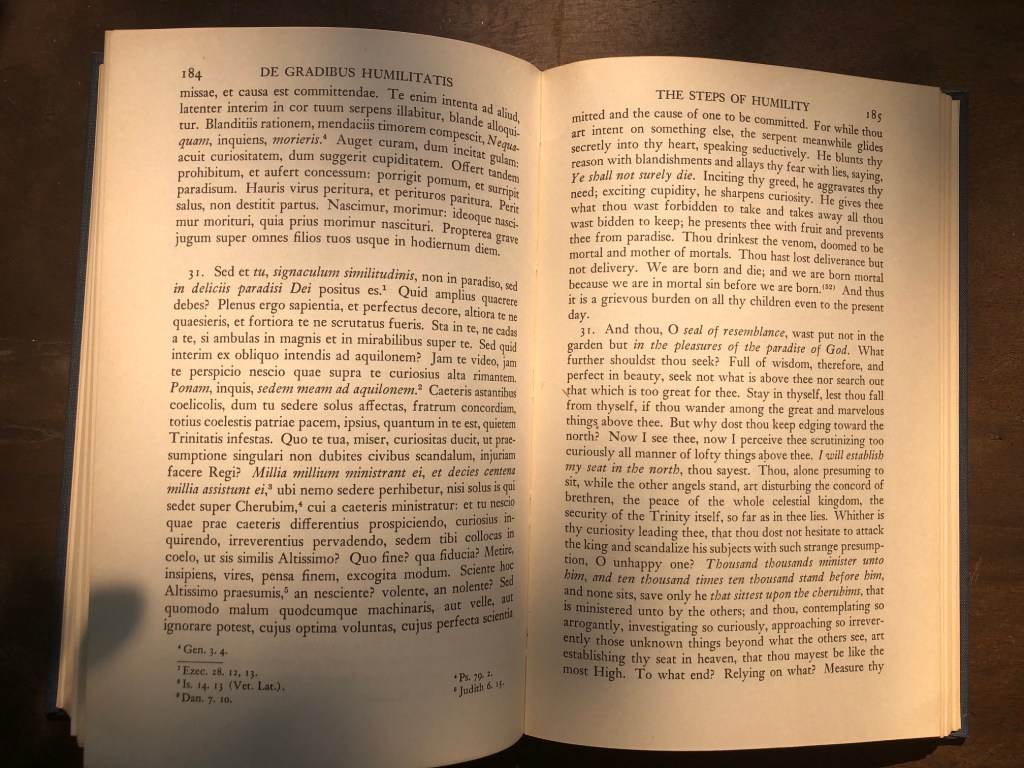

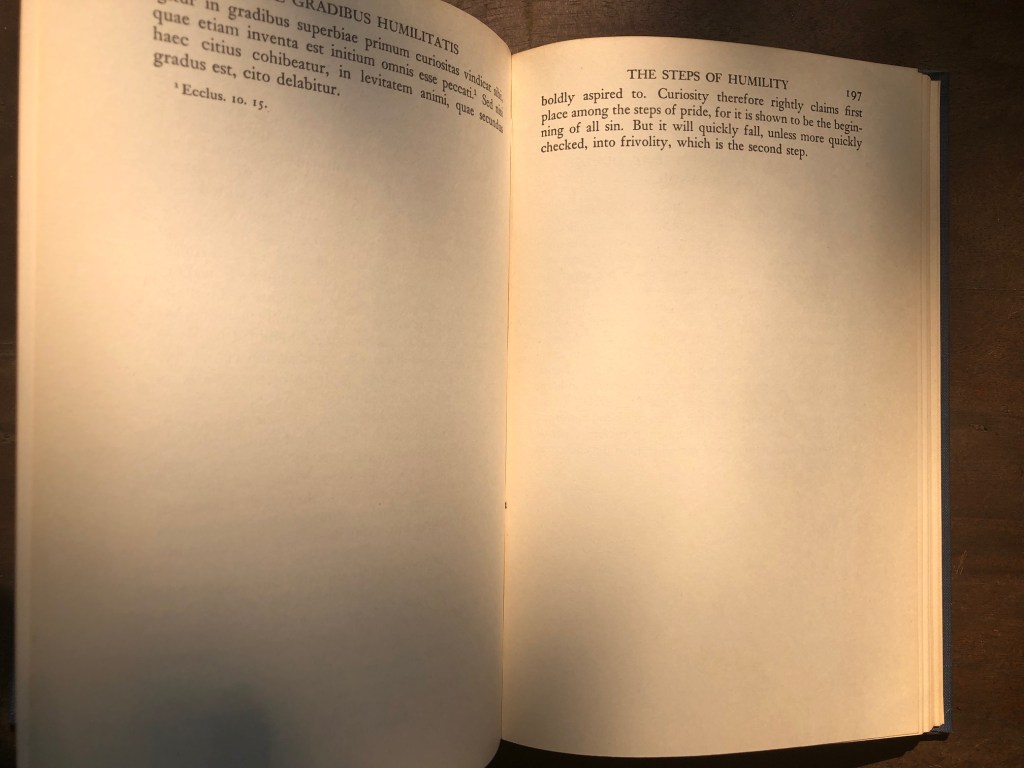

CHAPTER 10

THE FIRST STEP OF PRIDE, CURIOSITY

*

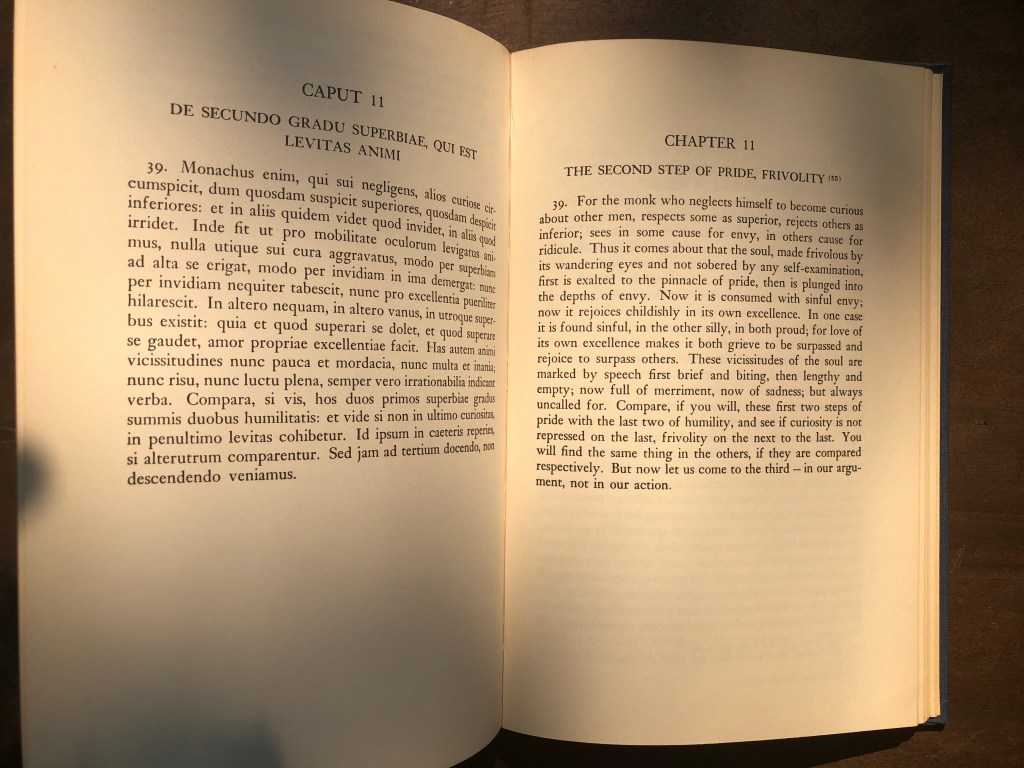

CHAPTER 11

THE SECOND STEP OF PRIDE, FRIVOLITY

*

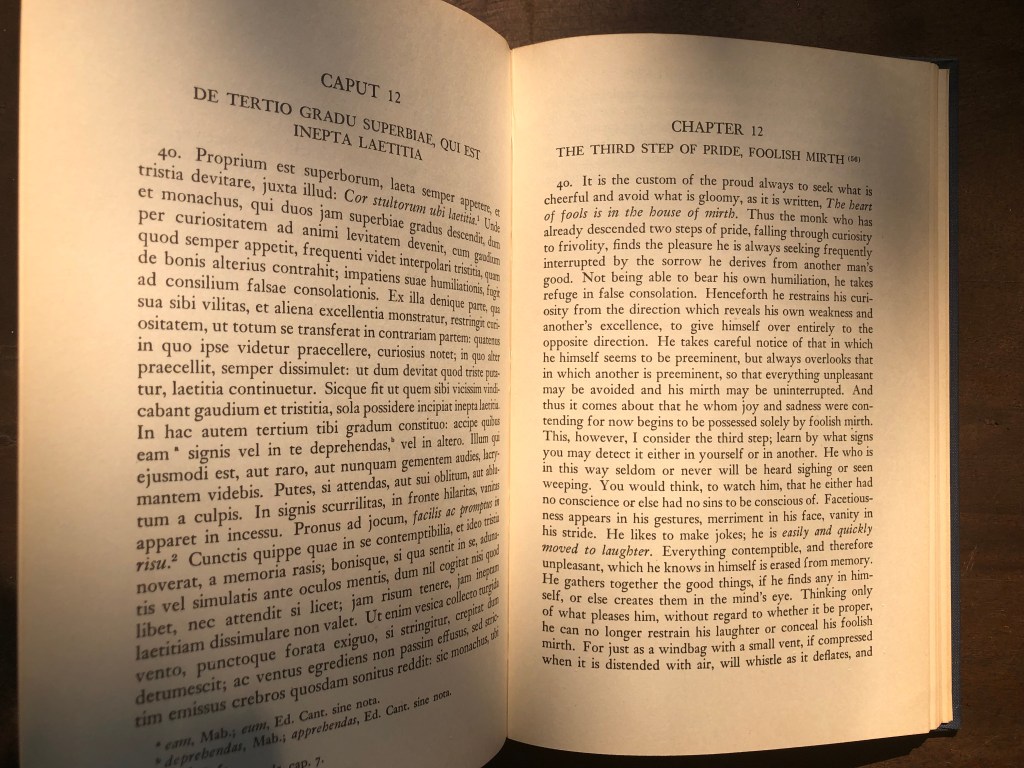

CHAPTER 12

THE THIRD STEP OF PRIDE, FOOLISH MIRTH

*

CHAPTER 13

THE FOURTH STEP OF PRIDE, BOASTFULNESS

*

CHAPTER 14

THE FIFTH STEP OF PRIDE, SINGULARITY

*

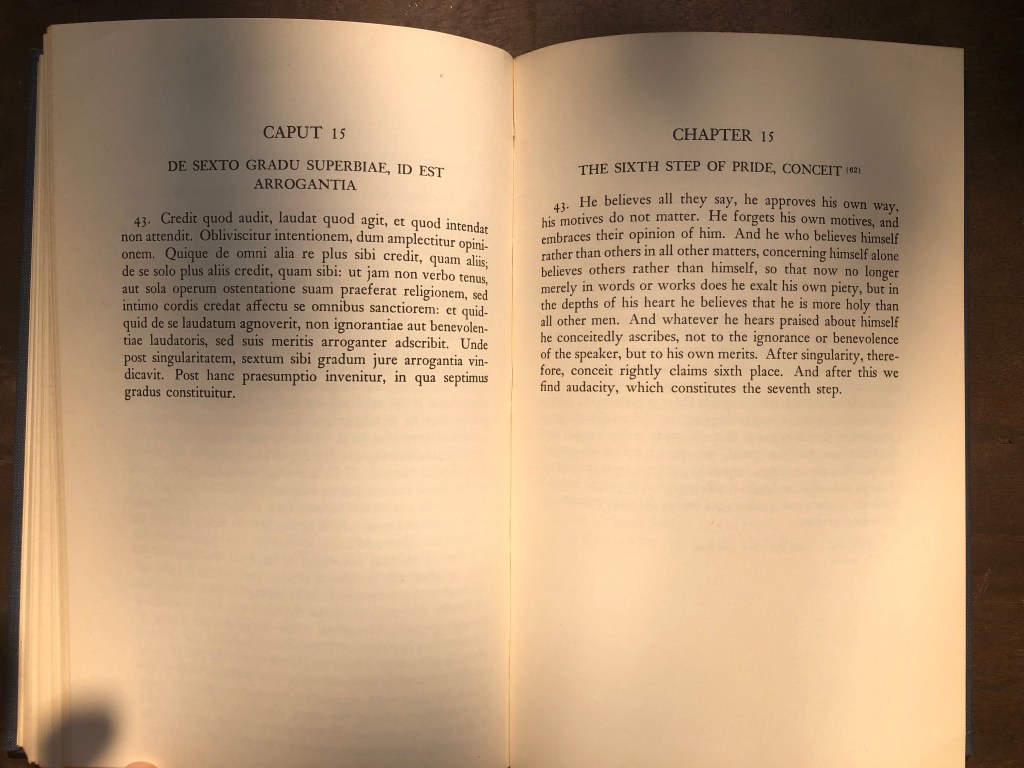

CHAPTER 15

THE SIXTH STEP OF PRIDE, CONCEIT

*

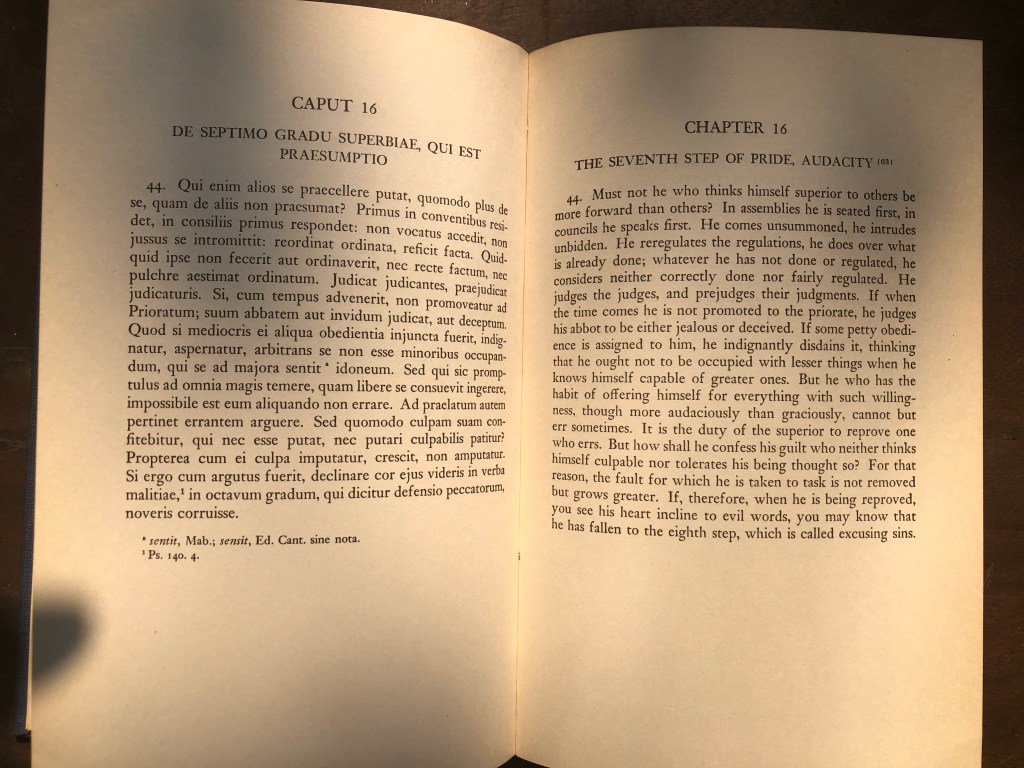

CHAPTER 16

THE SEVENTH STEP OF PRIDE, AUDACITY

*

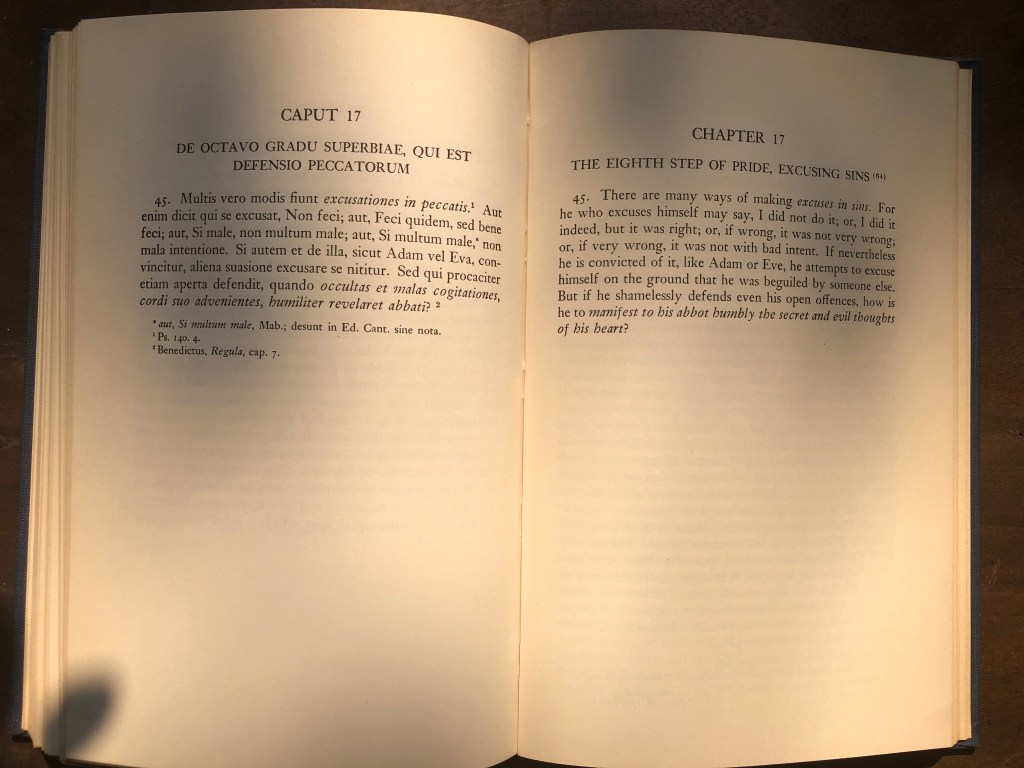

CHAPTER 17

THE EIGHTH STEP OF PRIDE, EXCUSING SINS

*

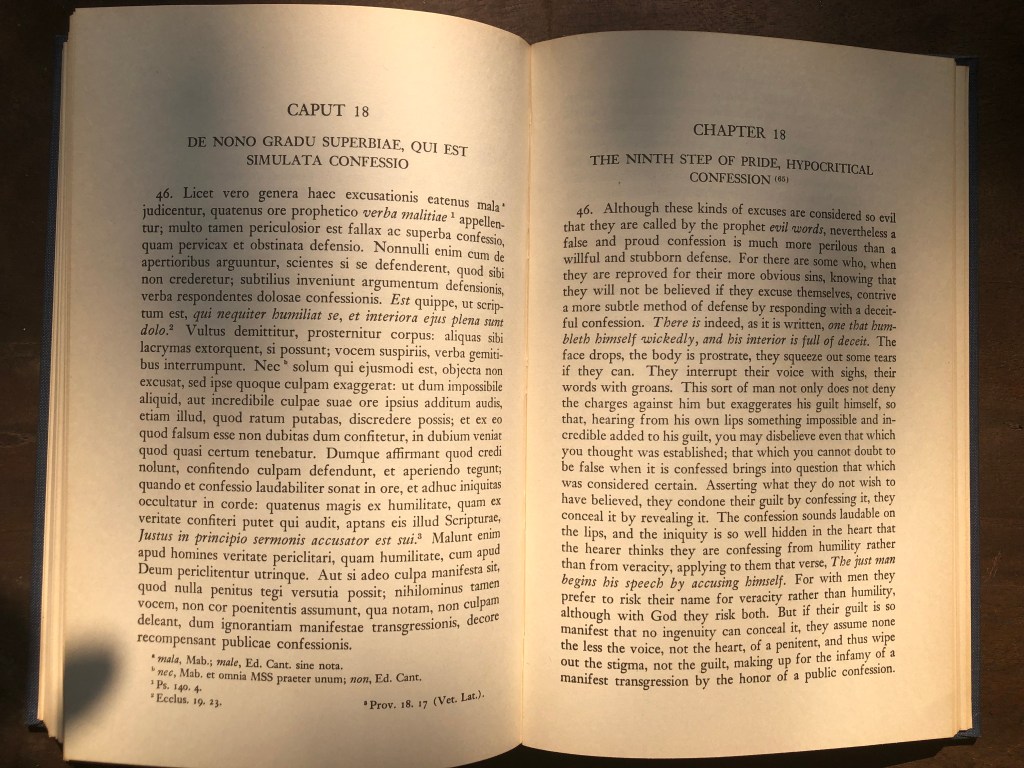

CHAPTER 18

THE NINTH STEP OF PRIDE, HYPOCRITICAL CONFESSION

*

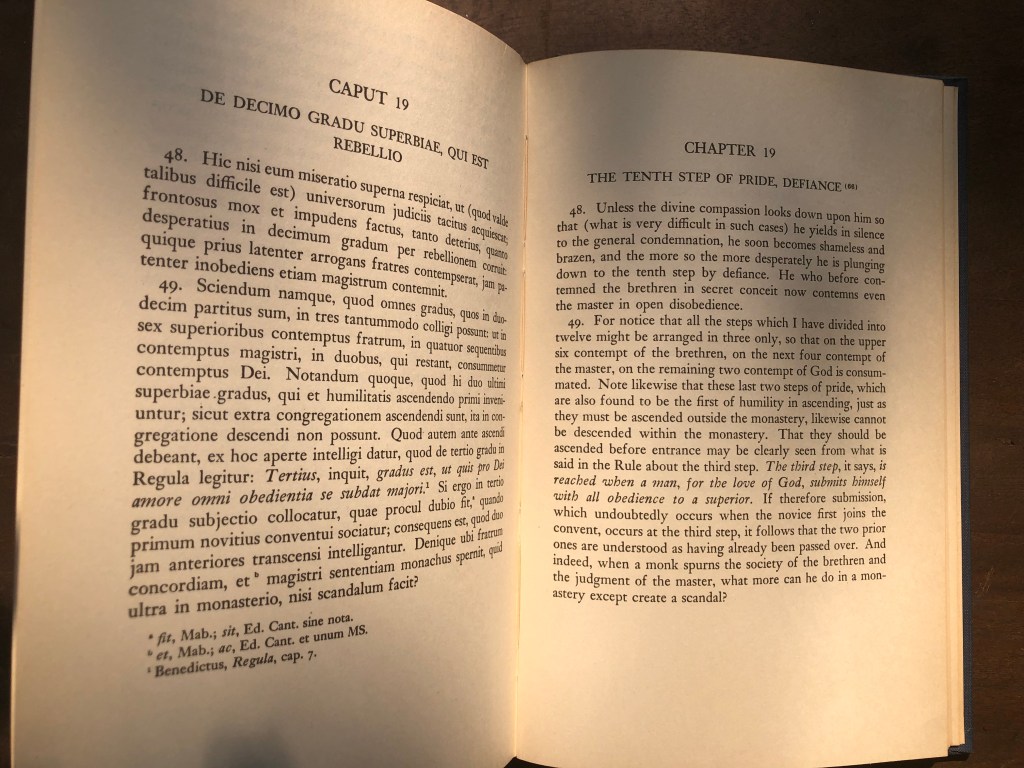

CHAPTER 19

THE TENTH STEP OF PRIDE, DEFIANCE

*

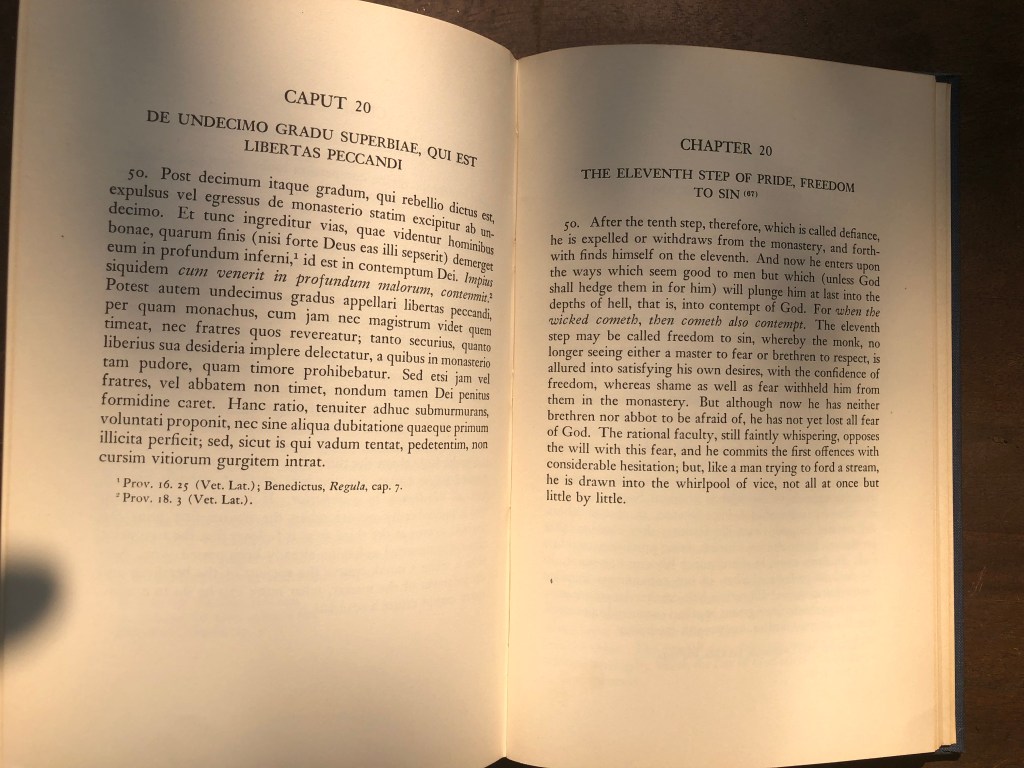

CHAPTER 20

THE ELEVENTH STEP OF PRIDE, FREEDOM TO SIN

*

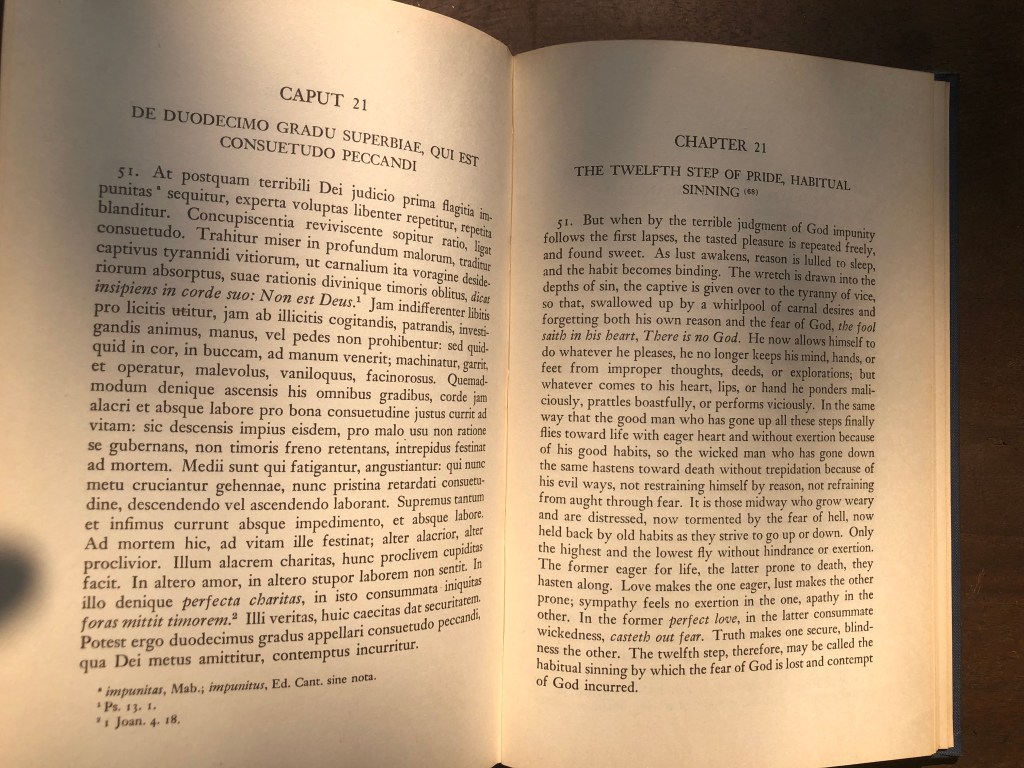

CHAPTER 21

THE TWELFTH STEP OF PRIDE, HABITUAL SINNING

*

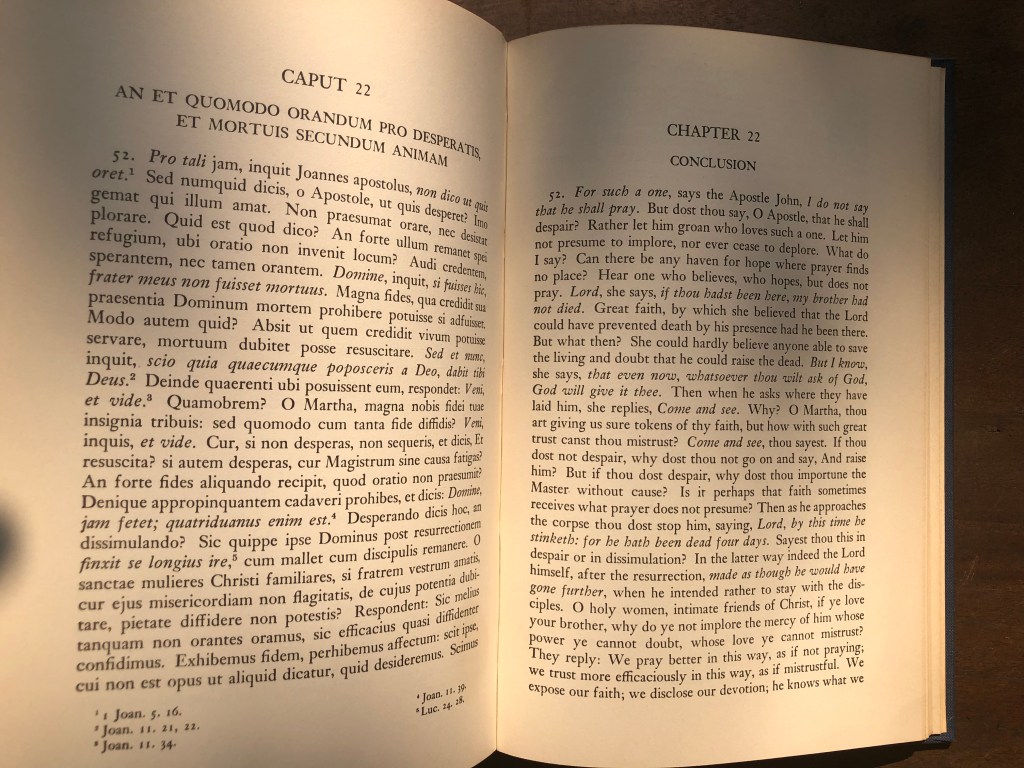

CHAPTER 22

CONCLUSION

*

Leave a comment