Friedrich Nietzsche

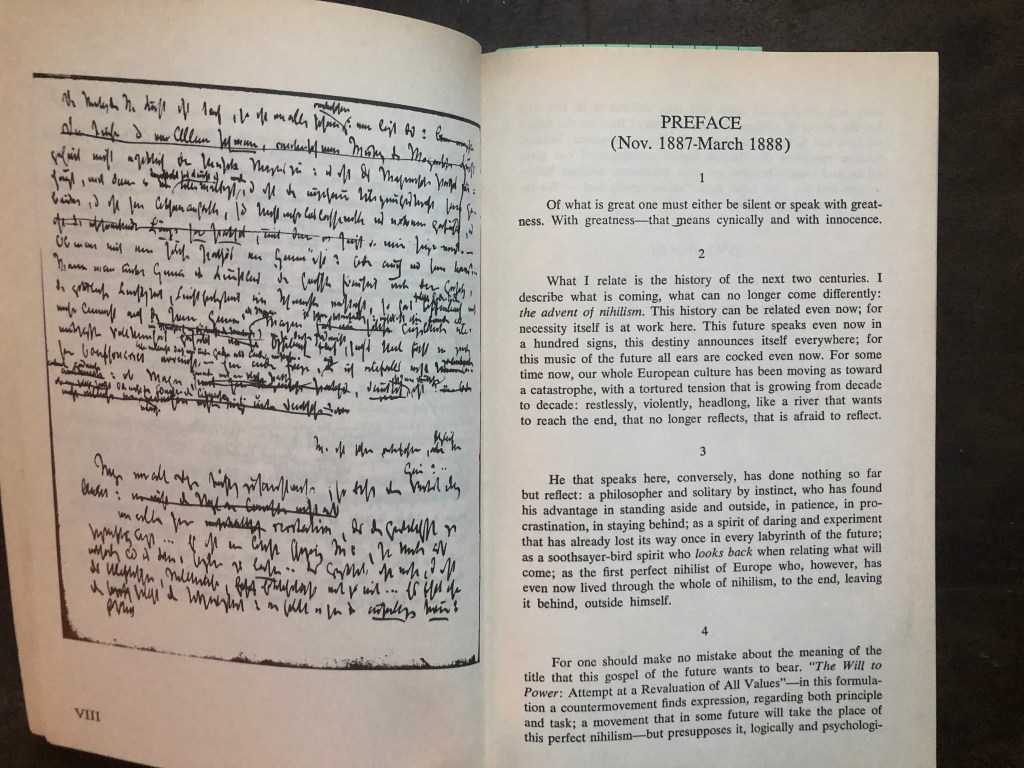

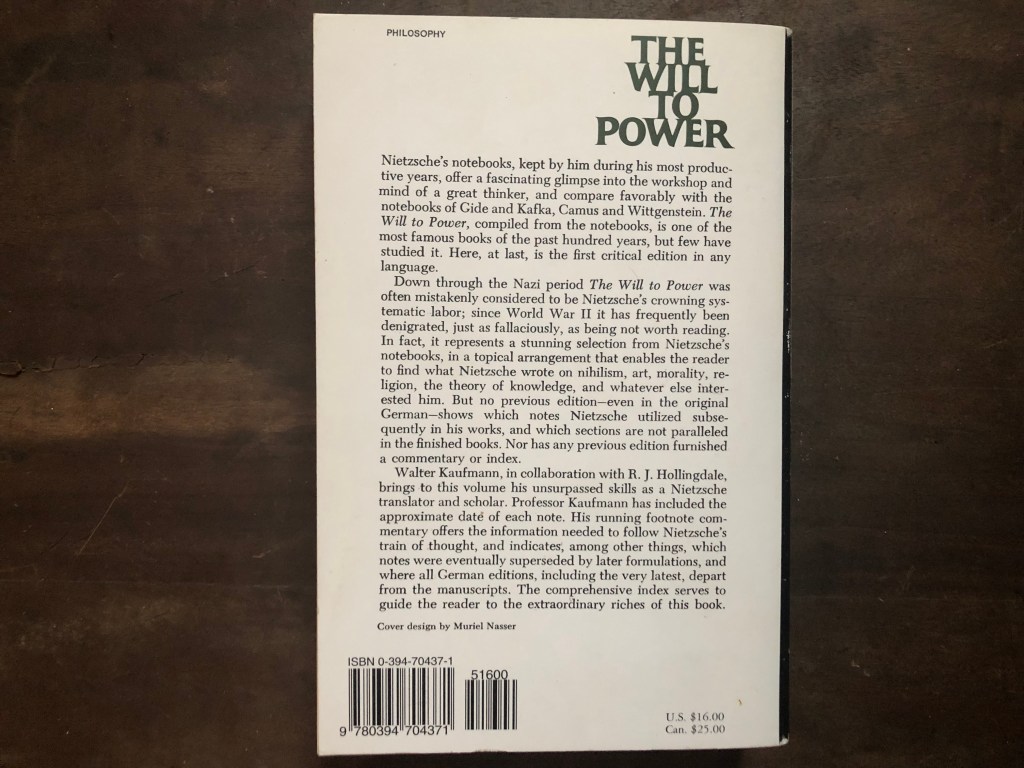

The Will To Power

Translated by Walter Kaufmann & R.J. Hollingdale

Edited by Walter Kaufmann

*

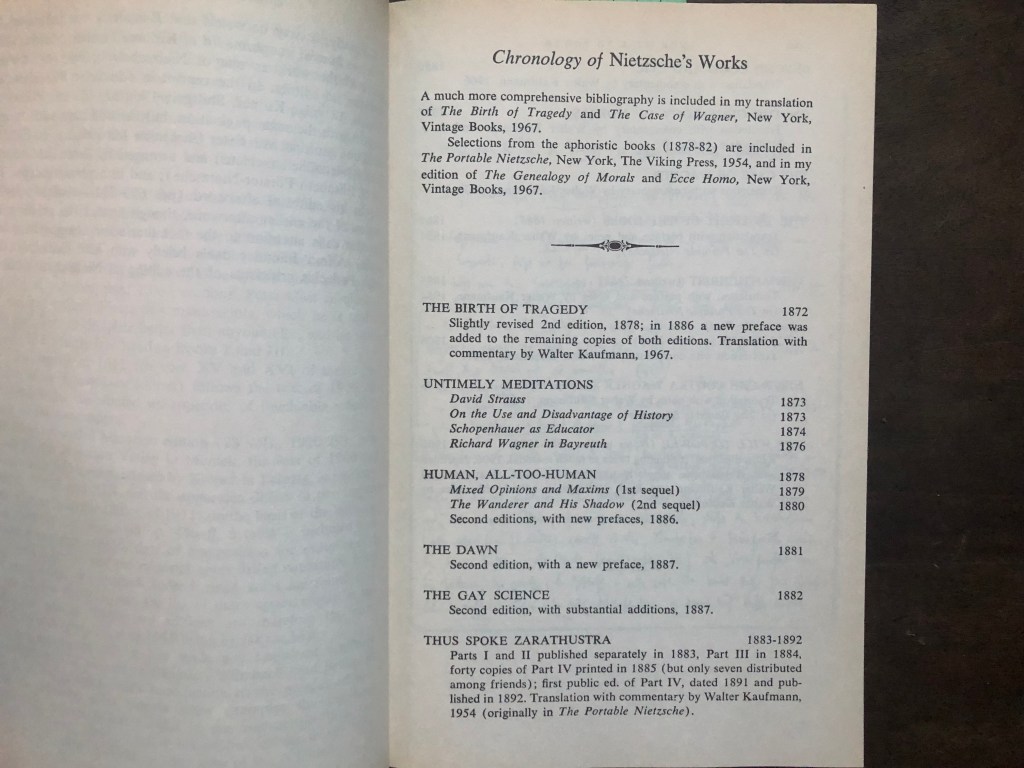

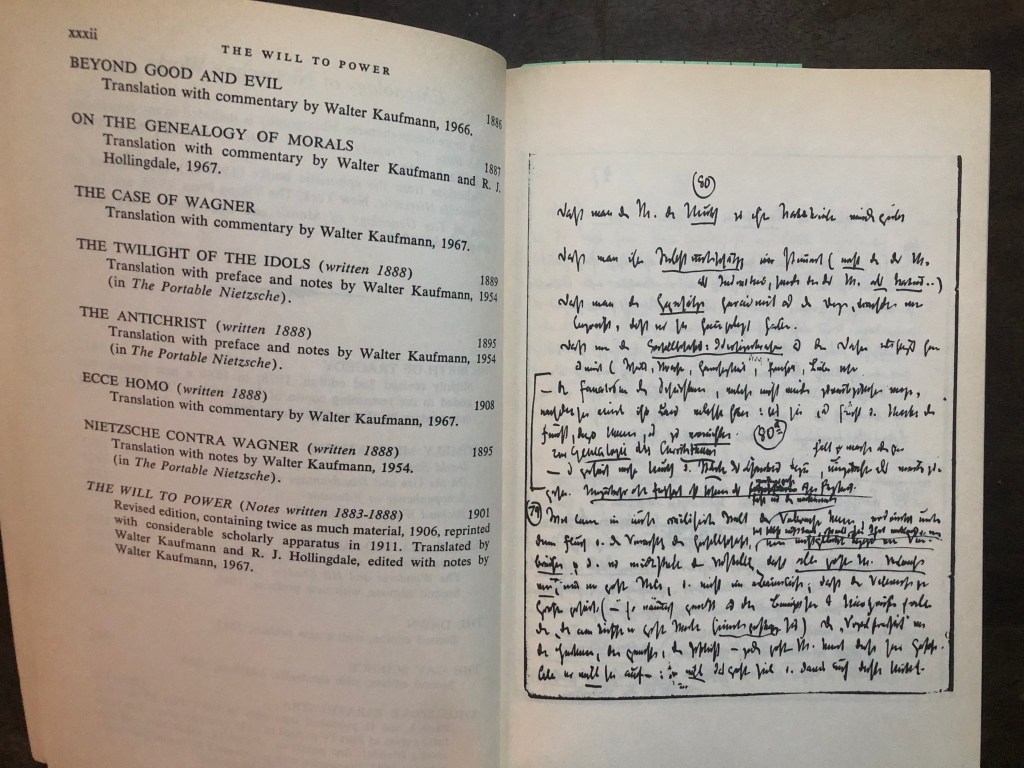

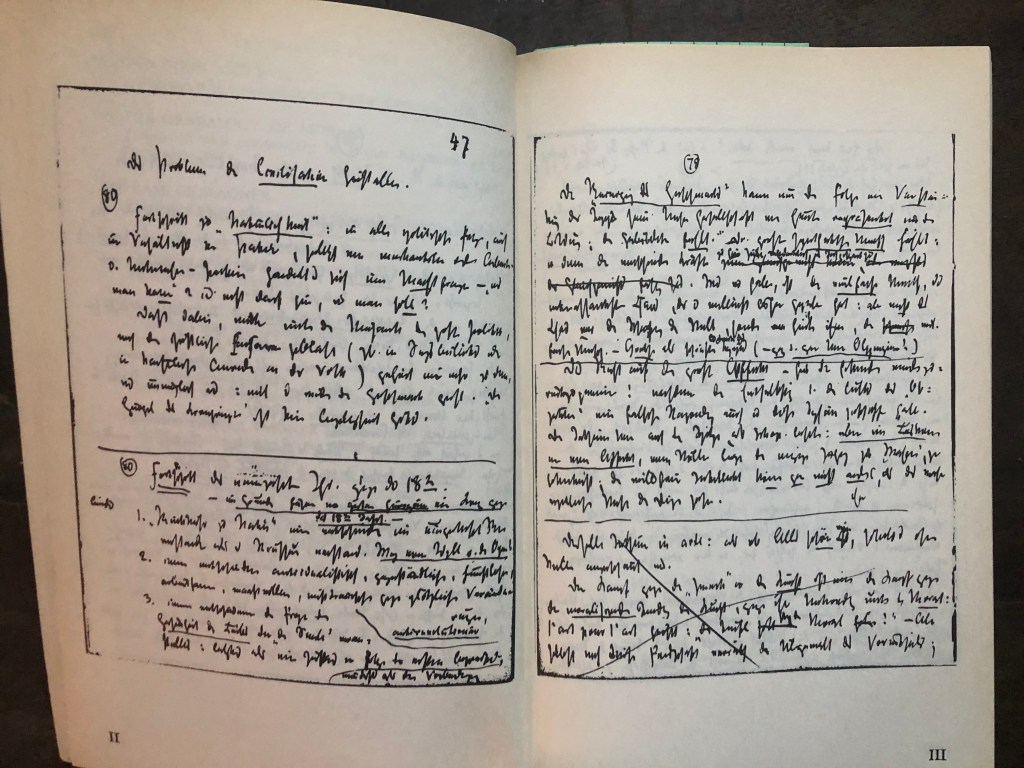

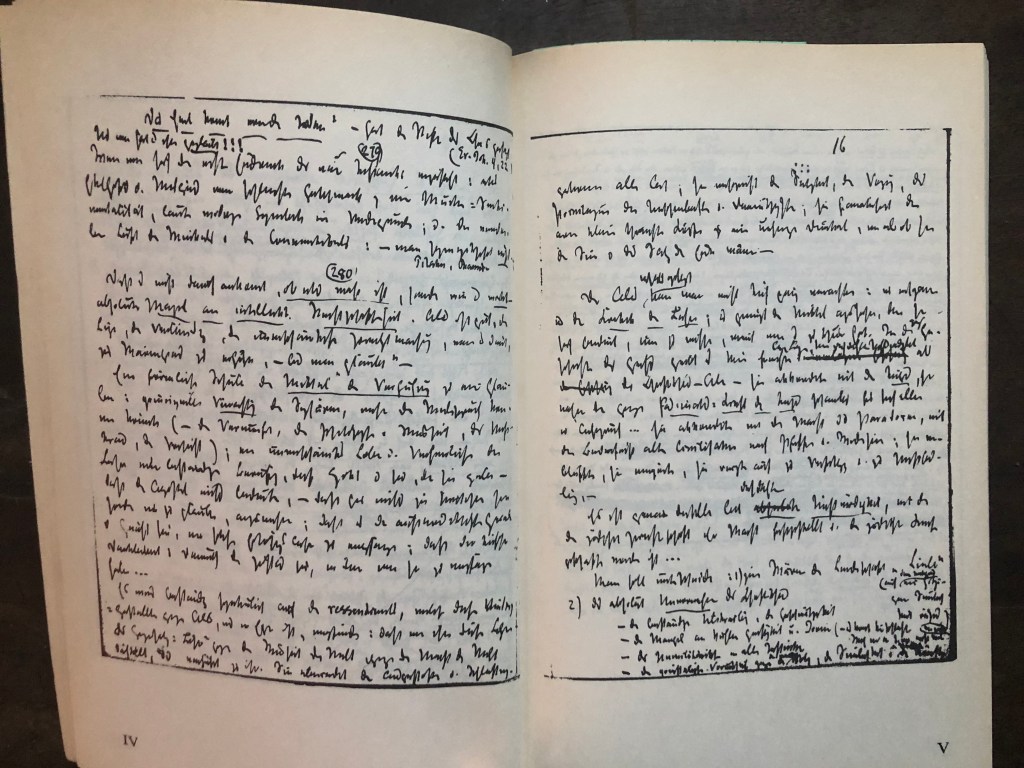

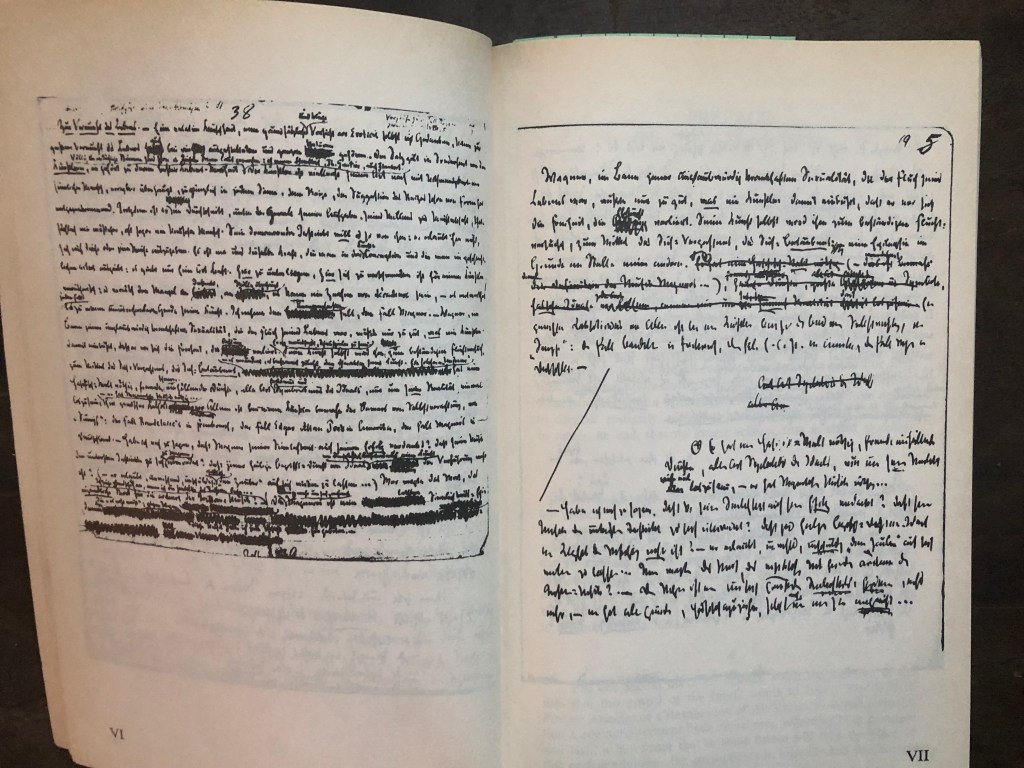

The Will To Power is technically a collection of Nietzsche’s notes. “Nietzsche had the habit of using over and over old notebooks that had not yet been completely filled, and of writing in them now from the front toward the back, now from the back toward the front; and sometimes he filled right-hand pages only, at other times left-hand pages only.”

It is important to recognize that the thoughts that follow come from Nietzsche’s notebooks and were organized by others after he was already mad. With that being said, I find it insightful to experience the sway of thoughts as they build and unfold, and leave off unfinished. The editors have inserted dashes — where thoughts trail off unfinished. Nietzsche used dots … to indicate that a thought was unfinished but in the typed format the “…” has become “—“.

I took this copy of The Will to Power off the bookshelf the other day and opened randomly to page 156, a section titled The Herd. I started reading and immediately recognized the deep resonant insights that feel all too timely in our current historical moment. I recently read a Bertrand Russel quote that read, “Collective fear stimulates herd instinct, and tends to produce ferocity toward those who are not regarded as members of the herd.”

In response to my experience with this text in the current historical moment, I’ve decided to type up this short section of Nietzsche working out his thoughts on The Herd and leave them here to be discovered again.

*

2. The Herd

274 (Spring-Fall 1887)

Whose will to power is morality? — The common factor in the history of Europe since Socrates is the attempt to make moral values dominate over all other values: so that they should be the guide and judge not only of life but also of (1) knowledge, (2) the arts, (3) political and social endeavors. “Improvement” the sole duty, everything else a means to it (or a disturbance, hindrance, danger: consequently to be combatted to the point of annihilation —). A similar movement in China. A similar movement in India.

What is the meaning of this will to power on the part of moral values which has developed so tremendously on earth?

Answer: — three powers are hidden behind it: (1) the instinct of the herd against the strong and independent; (2) the instinct of the suffering and underprivileged against the fortunate; (3) the instinct of the mediocre against the exceptional. — Enormous advantage possessed by this movement, however much cruelty, falseness, and narrow-mindedness have assited it (for the history of the struggle of morality with the basic instincts of life is itself the greatest piece of immortality that has yet existed on earth —)

275 (1883-1888)

Very few manage to see a problem in that which makes our daily life, that to which we have long since grown accustomed — our eyes are not adjusted to it: this seems to me the be the case especially in regard to our morality.

The problem “every man as an object for others” is the occasion of the highest honors: for himself —no!

The problem “thou shalt”: an inclination that cannot explain itself, similar to the sexual drive, shall not fall under the general condemnation of the drives; on the contrary, it shall be their evaluation and judge!

The problem of “equality,” while we all thirst after distinction: here, on the contrary, we are supposed to make exactly the same demands on ourselves as we make on others. This is so insipid, so obviously crazy: but — it is felt to be holy, of a higher rank, the conflict with reason is hardly noticed.

Sacrifice and selflessness as distinguishing, unconditional obedience to morality, and the faith that one is everyone’s equal before it.

The neglect and surrender of well-being and life as distinguishing, the complete renunciation of making one’s own evaluations, and the firm desire to see everyone else renounce them too. “The value of an action is determined: everyone is subject to this valuation.”

We see: an authority speaks — who speaks? — One may forgive human pride if it sought to make this authority as high as possible in order to feel as little humiliated as possible under it. Therefore — God speaks!

One needed God as an unconditional sanction, with no court of appeal, as a “categorical imperator” —: or, if one believed in the authority of reason, one needed a metaphysic of unity, by virtue of which this was logical.

Now suppose that belief in God has vanished: the question presents itself anew: “who speaks?” — My answer, taken not from metaphysics but from animal physiology: the herd instinct speaks. It wants to be master: hence its “thou shalt!” — it will allow value to the individual only from the point of view of the whole, for the sake of the whole, it hates those who detach themselves — it turns the hatred of all individuals against them.

276 (1886-1887)

The whole European morality is based upon what is useful to the herd: the affliction of all higher, rarer men lies in this, that everything that distinguishes them enters their consciousness accompanied by a feeling of diminution and discredit. The strong points of contemporary men are the causes of their pessimistic gloom: the mediocre are, like the herd, little troubled with questions and conscience — cheerful. (On the gloominess of the strong: Pascal, Schopenhauer.)

The more dangerous a quality seems to the herd, the more thoroughly is it proscribed.

277 (1883-1888)

Morality of truthfulness in the herd. “You shall be knowable, express your inner nature by clear and constant signs —otherwise you are dangerous: and if you are evil, your ability to dissimulate is the worst thing for the herd. We despise the secret and unrecognizable. — Consequently you must consider yourself knowable, you may not be concealed from yourself, you may not believe that you change.” Thus: the demand for truthfulness presupposes the knowability and stability of the person. In fact, it is the object of education to create in the herd member a definite faith concerning the nature of man: it first invents this faith and then demands “truthfulness.”

278 (1885)

Within a herd, within any community, that is to say, inter pares, the overestimation of truthfulness makes good sense. Not to be deceived — and consequently, as a personal point of morality, not to deceive! a mutual obligation between equals! In dealing with what lies outside, danger and caution demand that one should be on one’s guard against deception: as a psychological preconditioning for this, also in dealing with what lies within. Mistrust as the source of truthfulness.

279 (1883-1888)

Toward a critique of the herd virtues. — Inertia operates (1) in trustfulness, since mistrust makes tension, observation, reflection necessary; — (2) in veneration, where the difference in power is great and submission necessary: so as not to fear, an attempt is made to love, esteem, and to interpret the disparity in power as disparity in value: so that the relationship no longer makes one rebellious; — (3) in the sense of truth. What is true? Where an explanation is given which causes us the minimum of spiritual effort (moreover, lying is very exhausting); — (4) in sympathy. It is a relief to count oneself the same as others, to try to feel as they do, to adopt a current feeling: it is something passive compared with the activity that maintains and constantly practices the individual’s right to value judgments (the latter allows of no rest); — (5) in impartiality and coolness of judgment: one shuns the exertion of affects and prefers to stay detached, “objective”;— (6) in integrity: one would rather obey an existing law than create a law oneself, than command oneself and others: the fear of commanding —: better to submit than to react; — (7) in toleration: the fear of exercising rights, of judging.

280 (Spring-Fall 1887)

The instinct of the herd considers the middle and the mean as the highest and most valuable: the place where the majority finds itself; the mode and manner in which it finds itself. It is therefore an opponent of all orders of rank, it sees an ascent from beneath to above as a descent from the majority to the minority. The herd feels the exception, whether it be below or above it, as something opposed and harmful to it. Its artifice with reference to the exceptions above it, the stronger, more powerful, wiser, and more fruitful, is to persuade them to assume the role of guardians, herdsmen, watchmen — to become its first servants: it has therewith transformed a danger into something useful. Fear ceases in the middle: here one is never alone; here there is little room for misunderstanding; here there is equality; here one’s own form of being is not felt as a reproach but as the right form of being; here contentment rules. Mistrust is felt toward the exceptions; to be an exception is experienced as guilt.

281 (March-June 1888)

When, following the instinct of the community, we make prescriptions and forbid ourselves certain actions, we quite reasonably do not forbid a mode of “being,” a “disposition,” but only a certain direction and application of this “being,” this “disposition.” But then the ideologist of virtue, the moralist, comes along and says: “God sees into the heart! What does it matter if you refrain from certain actions: you are no better for that!” Answer: My dear Sir Long-Ears-and-Virtuous, we have no desire whatever to be better, we are very contented with ourselves, all we desire is not to harm one another — and therefore we forbid certain actions when they are directed in a certain way, namely against us, while we cannot sufficiently honor these same actions provided they are directed against enemies of the community — against you, for instance. We educated our children in them; we cultivate them — If we shared that “God-pleasing” radicalism that your holy madness recommends, if we were fools enough to condemn together with those actions the source of them, the “heart,” the “disposition,” that would mean condemning our own existence and with it its supreme prerequisite — a disposition, a heart, a passion we honor with the highest honors. By our decrees, we prevent this disposition from breaking out and expressing itself in an inexpedient way — we are prudent when we make such law for ourselves, we are also moral — Have you no suspicion, however faint, what sacrifice it is costing us, how much taming, self-over-coming, severity toward ourselves it requires? We are vehement in our desires, there are times when we would like to devour each other — But the “sense of community” masters us: please note that this is almost a definition of morality.

282 (Fall 1888)

The weakness of the herd animal produces a morality very similar to that produced by the weakness of the decadent: they understand one another, they form an alliance (—the great decadence religions always count on the support of the herd). In itself, there is nothing sick about the herd animal, it is even invaluable; but, incapable of leading itself, it needs a “shepard” — the priests understand that — The state is not intimate, not clandestine enough; “directing the conscience” eludes it. And that is how the herd animal has been made sick by the priest? —

283 (1883-1888)

Hatred for the privileged in body and soul: revolt of the ugly, ill-constituted souls against the beautiful, proud, joyous. Their means: inculpation of beauty, pride, joy: “there is no merit,” “the danger is tremendous: one should tremble and feel ill,” “naturalness is evil; it is right to oppose nature.” Also “reason.” (The anti-natural as the higher).

Again it is the priests who exploit this condition and win the “people” over. “The sinner” in whom God has more joy than in the “just man.” This is the struggle against “paganism” (the pang of conscience as the means of destroying harmony of soul).

The hatred of the average for the exceptional, of the herd for the independent. (Custom as true “morality.”) Turning against “egoism”: only the “for another” has value. “We are all equal”; — against privilege; — against sectarians, free spirits, skeptics; — against philosophy (as opposing the tool-and-corner instinct); with philosophers themselves “the categorical imperative,” the essence of morality “universal and general.”

284 (Sping-Fall 1887)

The conditions and desires that are praised: — peaceable, fair, moderate, modest, reverent, considerate, brave, chaste, honest, faithful, devout, straight, trusting, devoted, sympathetic, helpful, conscientious, simple, mild, just, generous, indulgent, obedient, disinterested, unenvious, gracious, industrious —

To distinguish: to what extent such qualities are conditioned as means to a definite aim and end (often an “evil” end); or as natural consequences of a dominating affect (e.g., spirituality) or expressions of a state of distress, which is to say: as condition of existence (e.g., citizen, slave, woman, etc.).

Summa: they are none of them felt to be “good” for their own sake, but from the first according to the standards of “society,” “the herd,” as a means to the ends of society and the herd, as necessary to their preservation and advancement, at the same time as the consequence of an actual herd instinct in the individual: thus in the service of an instinct which is fundamentally different from these conditions of virtue. For the herd is, in relation to the outside world, hostile, selfish, unmerciful, full of lust for dominion, mistrust, etc.

In the “shepard” this antagonism becomes patent: he must possess opposite qualities to the herd.

Mortal enmity of the herd toward orders of rank: its instinct favors the leveller (Christ). Toward strong individuals (les souverains) it is hostile, unfair, immoderate, immodest, impudent, inconsiderate, cowardly, mendacious, false, unmerciful, underhand, envious, revengeful.

285 (Sping-Fall 1884)

I teach: the herd seeks to preserve one type and defends itself on both sides, against those who have degenerated from it (criminals, etc.) and those who tower above it. The tendency of the herd is directed toward standstill and preservation, there is nothing creative in it.

The pleasant feelings with which the good, benevolent, just man inspires us (in contrast to the tension, fear which the great, new man arouses) are our own feelings of personal security and equality: the herd animal thus glorifies the herd nature and then it feels comfortable. This judgment of comfort masks itself with fair words —thus “morality” arises. — But observe the hatred of the herd for the truthful.—

286 (1883-1888)

Let one not be deceived about oneself! If one hears within oneself the moral imperative as it is understood by altruism, one belongs to the herd. If one has the opposite feeling, if one feels one’s danger and aberration lies in disinterested and selfless actions, one does not belong to the herd.

287 (1883-1888)

My philosophy aims at an ordering of rank: not at an individualistic morality. The ideas of the herd should rule in the herd — but not reach out beyond it: the leaders of the herd require a fundamentally different valuation for their own actions, as do the independent, or the “beasts of prey,” etc.

*

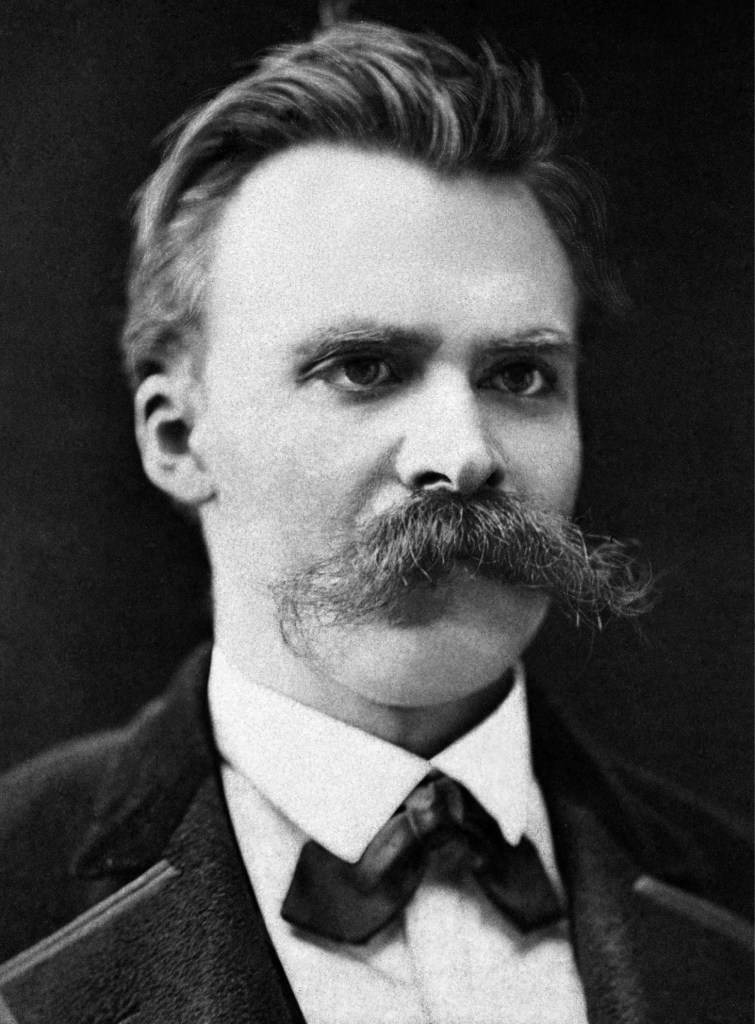

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900)

*

Leave a comment