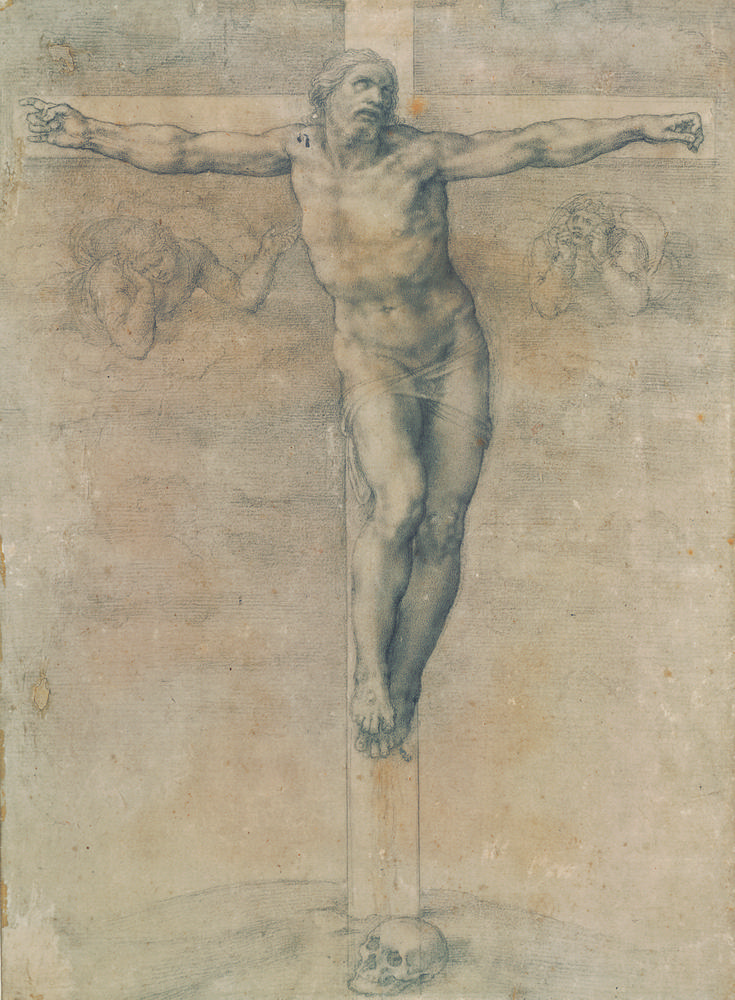

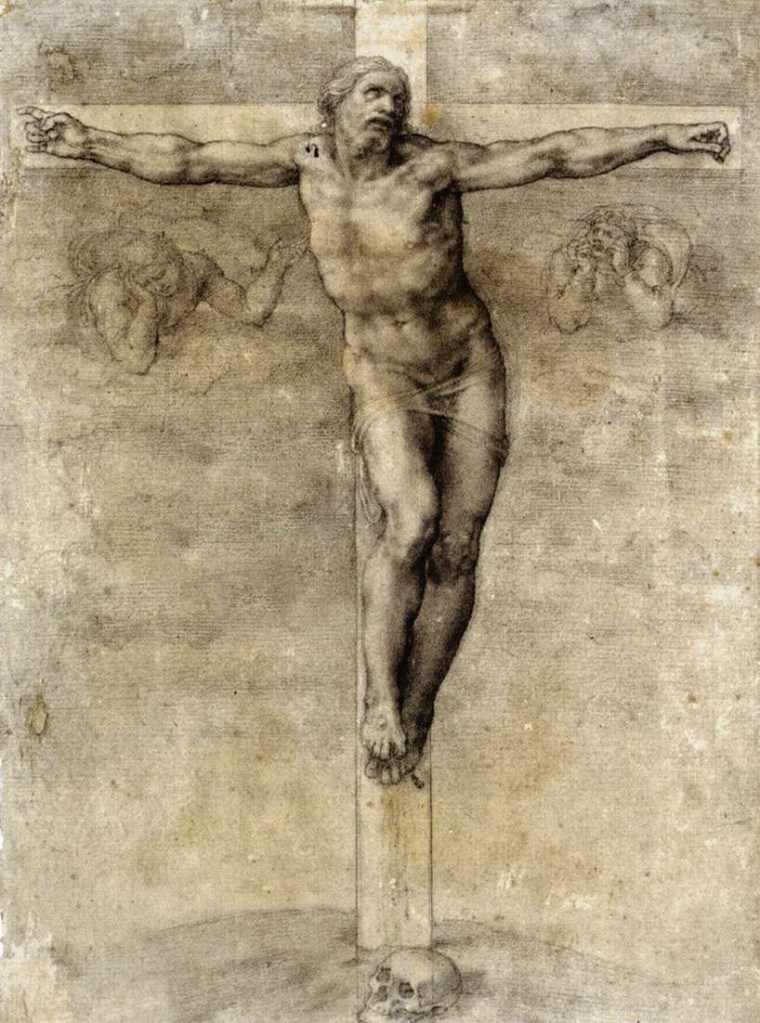

“It is thus quite appropriate that the final gesture of the dying hero in John Carpenter’s They Live is that of giving the finger to the aliens who control us – a case of thinking with a hand, a gesture of “Up yours!”, the digitus impudicus (“impudent finger”) mentioned already in Ancient Roman writings. The hand is here, yet again, an autonomous “organ without a body.” It is difficult to miss the Christological resonance of this scene of the dying hero who saves the world. No wonder, then, that in a unique moment in the history of art, the dying Christ himself was portrayed in a similar way. Wolfram Hogrebe proposed such a reading of Michelangelo’s unfinished drawing of Christ on the Cross which he first gave to Vittoria Colonna, his passionate intimate friend, and then inexplicably asked her to return it to him, which she refused to do, since she was enthusiastic about the drawing, and is reported as studying it in detail with mirror and magnifying glass – as if the drawing contained some forbidden half-hidden detail Michelangelo was afraid would be discovered.

The drawing illustrates the “critical” moment of Christ’s doubt and despair, of “Father, why have you forsaken me?” For the first time in the history of painting, an artist tried to capture Christ’s abandonment by God-Father. While Christ’s eyes are turned upward, his face does not express devoted acceptance of suffering, but desperate suffering combined with…here, some unsettling details indicate an underlying attitude of angry rebellion, of defiance. His legs are not parallel, one is slightly raised above the other, as if Christ is caught in the middle of an attempt to liberate and raise himself; but the truly shocking detail is the right hand: there are no nails to be seen, and the index finger is stretched out – a vulgar gesture which, according to Quintilian’s rhetorics of gestures probably known to Michelangelo, functions as a sign of the devil’s rebellious challenge. Christ’s “Why?” is not resigned, but aggresive, accusatory. More precisely, there is, in the drawing, an implicit tension between the expression of Christ’s face (despair and suffering) and of his hand (rebellion, defiance)- as if the hand articulates the attitude the face doesn’t dare to express. Did St. Paul not make the same point in Romans? “I take delight in the law of God, in my inner self, but I see in my members another principle at war with the law of my mind, taking me captive to the law of sin that dwells in my members.” Should we therefore not apply here to Christ himself his own “antithesis” from Matthew 18:9 – “And if thy right hand scandalize thee, cut it off, and cast it from thee: for it is expedient for thee that one of thy members should perish, rather than that thy whole body go into hell”? A passage which should nonetheless be read together with an earlier one (6:3) in which a hand acting alone stands for authentic goodness: “But when thou doest alms, let not thy left hand know what thy right hand doeth.” Is Christ at this moment, then, the devil; does he, for a moment, succumb to the temptation of an egoistic rebellion? Who is who in this scene of Goethe’s formula Nemo contra deum nisi deus ipse – no one but God himself can stand against God? But what if we follow, rather, the Gnostic line and conceive the God-Father himself, the creator, as the Evil God, as identical with the devil?”

Slavoj Žižek

The Monstrosity of Christ, pgs 277-278

THE MIT PRESS 2011

*

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1895-0915-504

*

*

Leave a comment